One of several papers on management

Why your volunteers are leaving

Written by John Berry on 12th November 2020. Revised 27th March 2024.

8 min read

Volunteers in youth work and other people-oriented charities have seen a huge upheaval in their worlds since lockdown was introduced in March 2020 to counter the coronavirus spread. There has been some indication that those volunteers quit their volunteer posts in significant numbers. Here’s a rationale to explain why volunteers left, and what might be done by whom in the volunteer agencies to cope better next time.

Volunteers in youth work and other people-oriented charities have seen a huge upheaval in their worlds since lockdown was introduced in March 2020 to counter the coronavirus spread. There has been some indication that those volunteers quit their volunteer posts in significant numbers. Here’s a rationale to explain why volunteers left, and what might be done by whom in the volunteer agencies to cope better next time.

Face to face

As a scenario for study, we consider here volunteer youth leaders delivering a service to young people while being supervised and supported by managers, some of whom may be volunteers themselves. Managers of volunteers typically look after anything from three to thirty youth workers across a geographic area. The youth leaders may, or may not, be grouped with one or two colleagues depending on the size of the local establishment.

Prior to March 2020, the volunteers met their young people face to face. And the managers had the opportunity to hold local meetings of several workers, while embracing low intensity computer-mediated communications. There was little, or no need, for the managers to give hugely of themselves, and the volunteers gained significantly from volunteer-to-volunteer support for joint activities and ideas sharing. Such a stasis existed for decades before.

In March 2020 the coronavirus pandemic struck and all changed. The whole of the UK was locked down. No volunteers were able to meet their young people. Some volunteers abandoned all contact, with groups suspended. Others embraced heightened computer-mediated communications to provide some limited programme via the Web. Something like just 30% of young people were reported to benefit from group meetings with their volunteers compared to pre-lockdown activity.

Around mid-year, some limited face to face activity was possible and slowly activities re-commenced. And then reports of workers quitting emerged.

Intention to quit

It’s well established that high-quality manager-volunteer relationships predict high volunteer performance. Typically, managers, aside from managing volunteer efforts, provide a range of services to volunteers and we discuss these further below. Conversely, it’s also well publicised that poor manager-volunteer relationships predict many undesirable outcomes – top of which is intention to quit. Intention to quit may not necessarily manifest in the volunteer quitting, particularly when there are other moderating factors.

Some volunteers can, of course, satisfy their own needs and function well without a manager. When it comes to driving a web-based programme delivery, they have the necessary skills. They typically have the ability to do the necessary research, relate to the young people and encourage some level of normality in difficult times.

Other volunteers were, however, in massively unfamiliar territory and were challenged. Lockdown was disruptive. For them, it stopped all activity.

Actually leaving

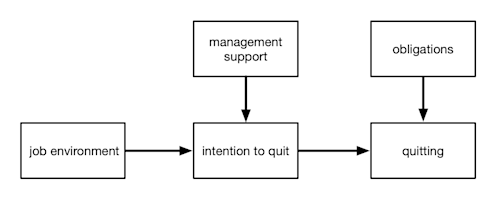

So how can we visualise this state where a volunteering job environment influences intention to quit in a volunteer, and ultimately causes some to actually leave the organisation and possible to leave volunteering altogether?

The model of this scenario is shown below.

It’s well established that negative aspects of the job environment influence the volunteer’s intention to quit. This negative influence is reduced by strong manager support. If manager support is not strong, the intention to quit may translate into the volunteer quitting. Typically, under normal circumstances, obligations felt by the volunteer stop those intentions being acted on. Simply, the feeling that the young people need the volunteer is enough to stop the volunteer quitting – even if the manager support is poor.

During the coronavirus pandemic, negative aspects of the voliunteer’s job heightened and were able to play on volunteers’ minds.

Focus on coping

First, government, through youth agencies, abruptly curtailed face to face youth meetings. Volunteers used to delivering face to face programmes had no outlet for their energies, and perhaps too much time to think.

Second, there were economic and social shocks on the volunteer and their family. Volunteering is something people sign up for to channel their spare emotions, energy and money. During lockdown, there was nothing spare and all energy and emotion was focussed on coping.

Third, and almost overnight, as youth work moved online, huge gaps in the volunteer’s competence in digital technologies became apparent. Volunteers were technically challenged, and failed to move to online provision. They looked toward managers for support, but they too were technically challenged and unable to help. These gaps heightened strain all round.

The result was a removal of obligations. Suddenly there were valid excuses to turn away from volunteering.

As a result, any intention to quit became a reality.

Manager action lacking

Arguably, this situation could have been averted. If volunteers felt that the negative aspects of the job environment were overpowering the positive, any development into intention to quit could have been moderated by increased manager support. Managers could have stepped up to the new challenge.

But they didn’t.

Firstly, managers needed to recognise that there was a problem looming and that action was needed to avert a potential existential threat (where lots of volunteers quit). Many didn’t realise this threat.

Secondly, managers would have needed the technical skills to come online and deliver new, invigorating programmes in a new environment. Senior managers in youth work did respond with centrally provide programme ideas. But there was little support from local managers. Many were technically challenged.

Thirdly, support requires the fostering of a dyadic – one-on-one – relationship. Success in dyadic relationships requires a particular personality – high extroversion and high agreeableness, for example. And success demands high interpersonal skills. Many managers simply didn’t have those in their repertoire and had never been trained to deliver supportive management.

Finally, there was significant confusion amongst managers about personal liability for coronavirus threat as preparations were made for return to controlled face to face activities. Some managers themselves quit.

Highlights

Now, theory tells us several things.

• High environmental strain causes high personal stress. Volunteers will make changes in their environment to reduce that stress. Quitting one activity (volunteering) is a way of being able to cope with others demanding attention and time.

• High job demands and low manager support leads to heightened intention to quit.

• High job demands and inadequate personal resources (in workers) leads to heightened intention to quit.

• Overcommitment – being the only person left to deliver after others have gone, and striving to do the work of two or three others – heightens stress, and in turn heightens intention to quit.

• If the volunteer ceases to get anything back from their volunteering, or perceives that they are not getting anything back despite expending effort, they will quit.

• Supportive management is, first and foremost, being there to listen. It’s giving advice, giving direct personal assistance, buffering volunteers from difficulties, smoothing the way through complex paperwork like risk assessments, training in new skills, coaching and providing emotional support.

• Supportive management is most essential during episodes of high emotional demand. Self-determined volunteers will flourish – until they can’t. There’s a strong link between volunteer motives and outcomes but this only sustains until interrupted.

• Successful supportive management depends on both frequency and quality of interaction. Some managers just can’t be supportive – it’s not in their make-up.

• Intention to quit is likely reduced with volunteer tenure – the greater the personal investment in the organisation, the greater the self-determination in volunteers.

• Intention to quit is reduced by strength in the demands-resources balance. The higher the skills and knowledge, the greater the ability to cope despite the change.

Theory suggests action. In a sense, though, it was too late for action after the event. It will take high personal effort by managers to get volunteers back.

Supportive management

As the pandemic evolved and new periods of lockdown were implemented, it was imperative that all managers of volunteers increased their level of supportive management. Many managers were not capable of doing this and themselves needed personal support.

Managers needed training in the relationship between job conditions and intention to quit, and the way that supportive management can moderate those intentions. It was critical that managers realised the effort needed here.

And they needed training in computer-mediated programme delivery.

Managers should have launched a huge initiative to show volunteers the value of what they do in order to tap volunteer intrinsic motives. It wasn't enough to espouse it. Communication should have been effective. Perhaps a thread here is the role of youth work in the nation’s non-formal education of young people and national recovery as a worthwhile cause.

All in all, recovery following such disruption needs highly effective supportive managers. This will take huge personal development for many, and no amount of espousing from the organisation senior managers can take the local manager’s place. It’s at the first tier of management where strength must first be built to acheive resilience for the next time.