Training as a means to an end not the end itself

The ongoing saga of training evaluation!

Written by John Berry on 27th November 2019.0

5 min read

There’s no doubt: ask any senior manager how he or she would evaluate training and the response will always be given in terms of how the business can now do something it previously couldn’t, or how productivity has been raised. It’s the effect on the business that matters.

There’s no doubt: ask any senior manager how he or she would evaluate training and the response will always be given in terms of how the business can now do something it previously couldn’t, or how productivity has been raised. It’s the effect on the business that matters.

The problem always is that there’s a time difference between someone doing training and the effect felt in the business. It could be months. It could be years. And there’s a huge amount that could go wrong in that time, resulting in outcomes not realised. If that happens, training is wasted.

In the middle, someone – a training advisor (TA) has to determine if the training was effective – often without actually knowing its real ultimate required effect. The TA plays a critical role in ensuring that the business outcomes will be realised but they often don’t make the link.

The TA can sign off competencies and behaviours acquired. And if the TA is not the manager, requiring and sensing the changed business outcomes, the jobholder may gain the training award, the new job and bigger salary but still fail to meet the newly acquired demands on them.

The weak links from need to outcome are in the quality of the TA’s knowledge about the business and in their judgement about the jobholder’s progress.

The emphasis here is that it’s outcomes that matter, not presence. Often, business outcomes are dislocated from the training results. Outcomes are sensed by the manager, not the TA.

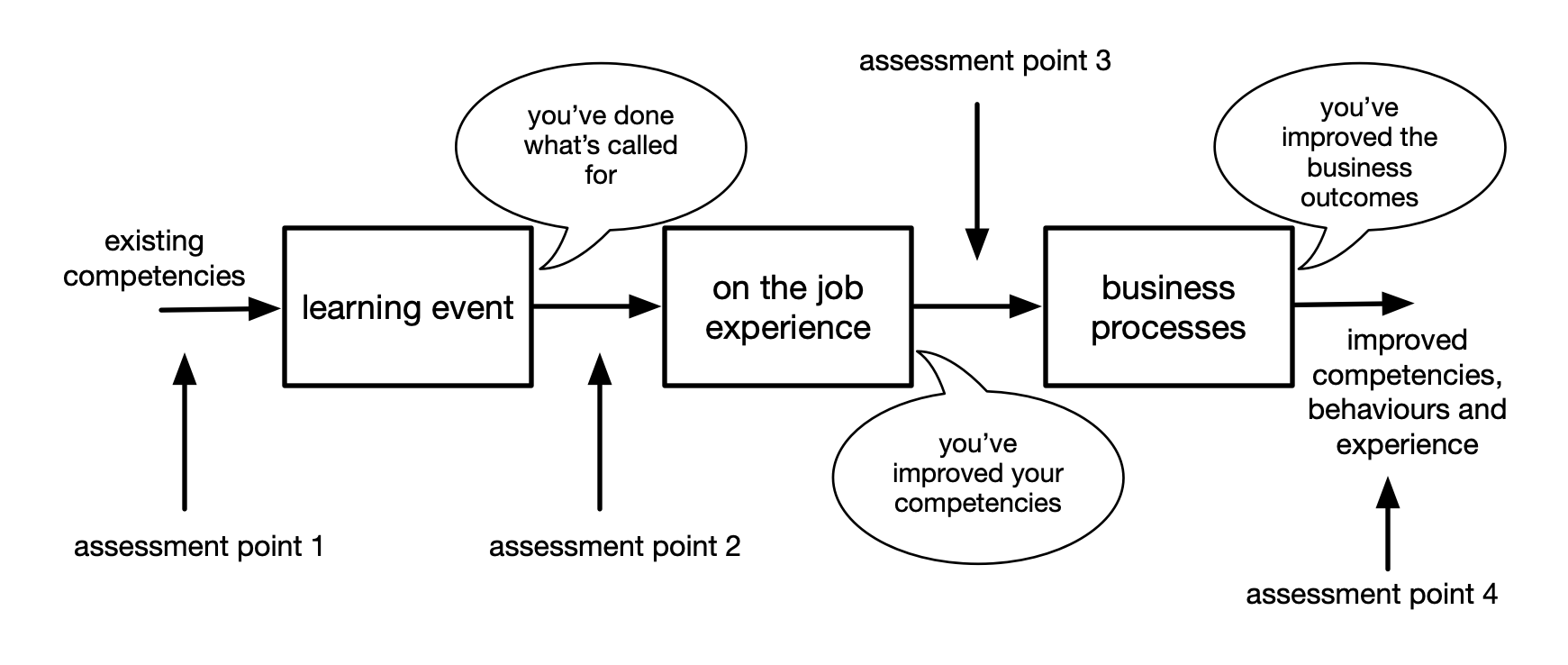

The diagram below shows the process from training to outcomes.

A jobholder enters the development process with existing competencies and behaviours. Given a certain technology, they have a certain capability (to do stuff).

The manager wants an improved business outcome. That’s the essence of the business case. A TA then translates what the manager wants into training events. He or she predicts that if this is done, the business outcomes will follow.

So, the first action is to determine what competencies and behaviours the jobholder needs to do this new stuff (assessment point 3). There are two routes to determining this: have a TA observe a suitably advanced jobholder and make a statement, or, determine the new competencies and behaviours by analysis.

The second action is to determine, using the same possible approaches, what relevant competencies and behaviours the jobholder currently has (assessment point 1).

The gap (between today’s competencies and behaviours, and those needed to secure the outcomes) is the development need.

It’s not the training need, by the way. Training is often just ‘sheep dipping’, giving the jobholder a training event or experience. Whether the jobholder as trainee develops depends on what happens during the event and after on appointment to the new higher job. The output of the training event is an interim state (assessment point 2).

Now, it’s at the output of the training event that most firms assess. It’s there that they tick the box.

Consider an example.

The requirement of the elevated job asks, “does the jobholder know how to write, manage the implementation of, and judge the effectiveness of project and/or development plans?”

This short phrase contains something like 20 discrete competencies and behaviours. For example, in order to be able to write development plans, the jobholder must understand where the organisation is today and know where it is supposed to be tomorrow. This action itself perhaps requires the jobholder to be competent in visioning. Then they need to be able to demonstrate behaviours that will lead to plan development.

So, the training event that is to cover how to write plans must be built from the specifically identified competencies and behaviours.

A tick box exercise will only confirm attendance at assessment point 2.

A TA must then make the judgement that the competencies and behaviours have been acquired. But this is huge ask, made incredibly difficult in any objective way unless the competencies and behaviours are documented.

The TA must talk to the jobholder (at assessment point 3) and conclude by discussion and observation if the jobholder does indeed know how to write plans. And there’s the flaw. Judgement of high-level statements like, ‘be able to write plans’, needs huge TA capability. And of course, some significant time must have passed since the training event to allow on the job experience.

Now, what matters is what improved business outcomes have been realised as a result of the training event (at assessment point 4).

If the TA ticks the box at assessment point 3, what’s to say that the jobholder’s business processes are such that their competencies and behaviours will be used. What’s to say that they will have opportunity and motivation to deliver the business outcomes?

This latter point can only be assessed by performance appraisal at assessment point 4 – and that requires agreement and commitment to suitable action. And the action, in our example, must require the jobholder to write plans.

So, to conclude.

Training assessment so often stops at assessment points 2 or 3. Have you been on the course? Have you been ‘dipped’? Some firms progress to assessment point 3 by asking a TA to judge. But that’s open to flaws unless competencies and behaviours are elaborate.

Few training assessments follow on to check if what the manager hopes for by way of business outcomes have actually been realised. And that’s where all should lead. After all, that’s all that matters. The rest is a means to that end.