On Health Screening and Other Employee Surveillance: A guide to introduction

On Health Screening and Other Employee Surveillance: A guide to introduction

Written by John Berry on 29th May 2017. Revised 25th March 2020.

14 min read

The Issue

There are a number of domains where management might want to monitor employees’ activities. Conversely, employees have the right to privacy whilst at work. Some examples of the arguments for and against are shown below.

| Desired Management Screening | From Management’s View | From the Employee’s View |

|---|---|---|

| Monitoring of company and private emails. | We must monitor to protect systems. | My private emails are private. I have a right of privacy. |

| Random drink and drugs testing. | We must be sure that all employees are sober. | If I have the odd drink in a day that’s my affair. |

| Monitoring employees’ health. | We need to be sure staff are fit to do the job. | My health condition is private, not for sharing. |

As individuals, we can all understand both sides of the arguments. Management can’t just bully staff to accede to intrusive screening, particularly where there is no obvious negative effect to employee performance. And conversely, where there is good reason for screening, employees can’t just say no to everything. The key to resolution is the phrase ‘good reason’. Management has a duty of care to its employees. That duty of care extends to being able to prove, possibly in a court of law, that it has taken such steps as necessary to protect staff and systems such that the business can continue to provide benefit to all its stakeholders. That duty of care gives management good reason but action must only be sufficient to control the problem and no more.

This paper shows then that management can’t simply start screening or surveillance. It must follow a process to prove that it is behaving reasonably to protect the business and stakeholders. That process has two aims: the first to show that the action is both necessary and proportionate and second to build trust in the staff who will be the subject of the action.

This paper goes on to take one of the common topics for surveillance, health screening, and uses that as example of how management should proceed.

Approach to Health Screening

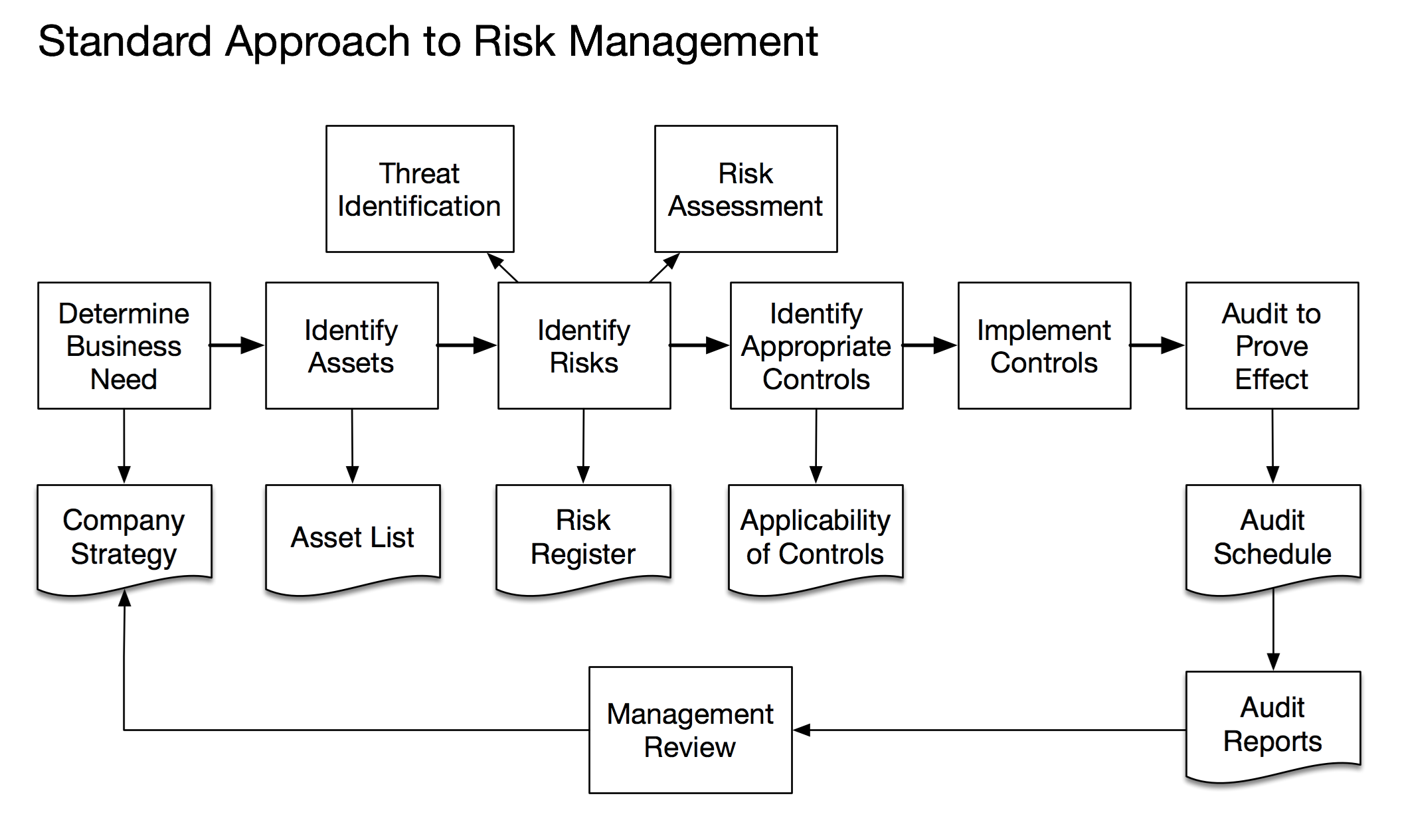

There is an established management approach to determining the actions that are needed to protect a firm. This applies in quality assurance, in information security, in health and safety and in a host of other areas that we normally see covered by various standards and institutions. It is the approach of risk management. The diagram below shows the essence of the approach.

There is an established management approach to determining the actions that are needed to protect a firm. This applies in quality assurance, in information security, in health and safety and in a host of other areas that we normally see covered by various standards and institutions. It is the approach of risk management. The diagram below shows the essence of the approach.

Determine Objectives

Let us assume that the firm is in a business that uses processes that might be a hazard to employees’ health. In this case there is perhaps some history that suggests that protection of the workforce is an issue or legislation may be in place[1]. Management in their strategy should determine objectives that express the desire to control risks. In health and safety the Health and Safety Executive give guidelines. These objectives are likely to be compliance with HSE guidelines or measurable targets from other agencies[2]. The assets in this case are human – staff. Management is acting to protect its assets. It is not acting to protect itself from lawsuits. If it protects its staff, there will be no lawsuits.

Hazards

The second activity is to draw up a risk register by investigating the processes undertaken by the workforce. A risk register is a list of the untoward events and hazards that might beset the assets (the workforce) when running the process. Once the list is available, each can be scored for chance of occurrence and severity of effect. A final score is arrived at by multiplying the risk by the severity. Only risks scoring over a value (decided on by management) are mitigated. The rest are accepted. How this is done is well documented[3].

Many risks to health occur when exposure is over a long period. The effect must therefore be assessed considering ‘normal’ operation. An example might be use of hand tools which vibrate and where normal use is near-continuous. The effect is felt in time by the operative.

Controls

The process of risk management then requires the company to determine the controls needed to reduce the effects of the various risks to acceptable levels. These acceptable levels or in the case of exposure, exposure action values (values above which management must act to control) are key to risk management. No risk will ever be eradicated but all can be managed. In the above example a simple control might be to reduce the time taken using the vibrating tool. This may demand use of an alternative low exposure tool in order to run the process and the risk has been managed to below the exposure action values. Controls manage risks.

Maintenance

And finally, management must be able to prove that the risks are maintained below accepted levels or exposure action values. It’s here that health screening might play a part but only after the risks have been identified and the controls put in place. Management must keep records and these records must be proven valid. In the case of the vibrating tool, a simple paper log of the number of hours a day each employee uses that tool might suffice. This can be captured from time to time and presented graphically to show that the control is working. Audit involves inquisitorial investigation to determine if the records are true – often by simply asking the employees, then observing the process to see that it can be completed without falsifying records. The best auditors are other staff from other departments. Modern methods of audit are well documented.

Screening

Health screening can be part of the process and provides measurement – and measuring health deterioration should drive modified controls. But it does not replace other measures and controls. In the case of non-ionising radiation (cited above as a footnote), we don’t go measuring employees for cancer. We control exposure levels. If health effects are seen, one could argue that it’s too late. Ultimately then, management should be able to confirm that the controls are in place. They can underpin their assertion that the process is safe by referring to the body of knowledge that exists, for example about the effects of vibration and the exposure action values. And in some cases, perhaps where the effects are so severe and difficult to measure[4 ] or perhaps where the body of knowledge does not exactly apply to the industry or is as yet not conclusive, additional security may be needed to show that the duty of care has been discharged. In this case, management may implement screening for specific health symptoms identified when analysing the effects during risk analysis. By identifying the risks, controlling them and identifying occasion when control may fail or be inadequate, management has demonstrated necessity and proportionality.

Interim Conclusions and Recommendations

We have demonstrated that surveillance and specifically health screening is one part of a management process that starts with the firm’s board of management determining strategy and ends in controlling the chance of untoward events and reducing the effects of exposure to hazards. In many cases, the effects of these untoward events and the effect of prolonged exposure on the health of workers can be controlled by changing the process or perhaps having operatives wear personal protective equipment.

In the first part of this paper we don’t discuss how surveillance or health screening might be introduced – for there are many problems. The positive psychological contract between staff and the firm can easily be destroyed by mandatory and potentially unnecessary screening. We started this paper with a discussion about how employees feel about such management action. Part of the process of introduction is the proof to staff that management is discharging its duty of care; that it is determining what is necessary and proportionate to safeguard employees’ health. That done, it can legitimately begin the process by which it will introduce screening should that be necessary.

There’s still a long way to go before staff will be happy to submit to screening. We discuss the employee relations issues in the next part.

Do ask us any questions about the approach to screening and surveillance outlined here. We can guide you every step of the way in introducing screening and surveillance. Call us or email us for a discussion about your issues.

The conditions for introduction

Staff have an option when it comes to reacting to any change in the workplace, and this includes the implementation of surveillance. They can accept the change and work with it as a continuation of the existing management systems. This is of course what management want, but not what they are guaranteed to get. Alternatively staff can accept the change reluctantly. Or they can work round the surveillance, learning to circumvent its monitoring and intrusion, to the point that the staff control the surveillance. Or they can reject it outright and refuse the modified terms and conditions of employment, forcing management into a difficult disciplinary battle that they might well loose. The reaction from staff depends on the trust relationship in the firm. And trust depends on the culture in place. So whether the introduction of surveillance will be successful depends much on the culture in the firm.

Systems, trust and performance

Trust is the belief that the employer will be honest and follow through with commitments. Trust is central to the culture that exists in a firm. Trust between management and workforce influences performance-related business outcomes like customer satisfaction, growth and profit. There is a strong link between management systems (and we include surveillance as one such system) and performance.

Surveillance of staff for whatever reason is synonymous with performance. Management want to implement surveillance because it believes that to do so will improve performance. It may be surveillance to avoid reduced lost time due to drink and drugs or monitoring employees’ online activities to stamp out wasted time on social networking sites. Performance is the central aim. So performance depends on both trust and management systems but there is no research that connects trust and management systems directly. Both remain the independent variables in their independent relationships. An increase in trust between employees and management raises performance. And independently, an increase in effectiveness of management systems raises performance.

Causes and relationships

Were it simply the case that trust and management systems were independent, management could proceed to implement surveillance without further concern about performance reduction. Implementing a management system like surveillance, however, erodes trust. A perception that surveillance is needed suggests to staff that they are not trusted by management. Management control replaces trust.

In effect therefore trust and management systems are linked. Introduction of a controlling system may enhance performance directly but it risks degrading trust. So to avoid eroding the trust to the performance relationship, only appropriate management systems can be employed. And if a management system that might be viewed as trust-eroding by staff is deemed necessary by management, there must be enough trust capital in the minds of staff to overcome negative fears and beliefs. Staff must be able to trust management that the system being installed is necessary, appropriate and will not lead lead to erosion of rights currently enjoyed.

The meaning of trust

For management to build trust it must have a track record of repetitive action that yields consistent results. Trust comes from five management activities:

Concern for employees

Caring for staff when they feel vulnerable in an organisation. Such a state exists of course when implementing surveillance. It means having empathy with staff. It means having tolerance. It means being sensitive to people’s needs.

Openness and honesty

Being open and honest means providing accurate information on the state of the company. Providing accurate information on the needs for surveillance will help staff understand but will also build belief that management are open and honest. Open and honest consultation with staff when implementing surveillance or monitoring is essential in maintaining trust.

Identification

Identification requires both staff and management to share the same goals, norms and values. If there are no common goals, management and staff becomes ‘them and us’. Common goals generates a shared language and aids discussion. Participation in the firm and its goals leads to commitment.

Reliability

For reliability, management must have a track record of making and reliably following through with decisions and actions. If management are unreliable, any change will be considered as just another management fad. This erodes commitment to any subsequent action.

Competence

This final category requires management to be competent. This competence extends in this case to implementation of surveillance. For competence to build trust, management will need to have the expertise, knowledge and abilities such that they can make the implementation a success from which all will benefit. Staff must not believe that it will just be another management disaster.

Effects of culture

Some firms lend themselves naturally to higher trust. In firms where jobs are flexibly defined and where staff are given broad objectives, trust tends to be easier to build. Trust is also enhanced where there is good flow of information both about the company and its fortunes and about the tasks and customers (and of course about the need for surveillance and monitoring). Trust is also enhanced where staff are expected to take risks in completing their work, perhaps buying new tools or contracting work out in order to meet customer needs.

Firms, on the other hand, that have a process-driven activity where jobs are rigidly defined and staff are managed to ensure compliance with procedures tend to find it more difficult to build trust. There is less information flow with staff only told what’s needed to do their job. Information flows from the top down and is filtered and reduced as it goes. Management systems are used in these firms to control and surveillance would be seen by staff as another such system. The culture in the firm has a significant impact on trust building. The former type of culture, called organic culture, tends to encourage growth of trust. In the latter, called mechanistic, trust is much more difficult to build.

Health screening and other employee surveillance

There are strong relationships between trust and performance and between effective management systems and performance. But implementation of some systems, such as surveillance, will be seen by staff as increasing management control. They will be seen as moving the firm from an organic culture to a mechanistic culture. They will therefore erode trust. And erosion of trust leads to eroded performance.

Now, this does not mean that management should always strive for an organic culture with few management systems and specifically no surveillance or monitoring.

The structures and business processes needed by a firm may be set by the market and customers or by regulators. What it does mean is that management must naturally build trust through their genuine concern for employees, openness and honesty, identification (with common goals), reliability and competence. That done, enough trust capital will have been built to enable surveillance to be introduced without undue reduction in performance.

So in simple terms, before introducing surveillance of any type, build trust. If introduction of surveillance is needed immediately, make such change as is possible to move towards an organic culture where information flows and staff have as much say as possible in how they do their job. Then take a trust-building strategy to overcome any trust reduction caused by the surveillance.

If you find this subject interesting and would like to discuss it more, do contact us.

- In the case of non-ionising radiation as an example of a hazard, no effects are seen immediately and indeed the current body of knowledge suggests that the risk to human health caused by direct heating and the body’s reaction to the radiation is very low and acceptable. However, the World Health Organisation recommends that because health effects could take fifty years to surface, firms employing technicians who operate in the ‘reacting’ and ‘radiating’ near-field (within a few meters of transmitting antennas) should act to protect. The accepted wording is ‘in the absence of scientific consensus (of effects and adequate controls), act to protect’. The ICNIRP guidelines therefore remain. In health protection, there are many such examples where firms should ‘act to protect’.

- See the HSE publication Five steps to risk assessment at http://www.hse.gov.uk/pubns/indg163.pdf though the process described is not adequate when dealing with risks in information security where risks are asset-specific.

- The COSHH Regulations 2002 cover working with substances that may be hazardous to health and the HSE booklet at http://www.hse.gov.uk/pubns/indg136.pdf gives guidance.

- A good example of risk management is the well structured approach to controlling exposure to non-ionising radiation covered by the guidelines from the International Commission on Non-ionising Radiation Protection (ICNIRP). To give examples of exposure action values, a technician near a cell phone mast should not be exposed to a specific absorption rate (SAR) of more than 0.4Watts per kilogramme weight for more than 6 minutes at a time. The SAR in W/kg can be calculated or a proxy of electric field strength in Volts per metre can be used. Measurement instruments can measure V/m where W/kg is more problematic.