Employing contractors and agency workers

Employing contractors and agency workers

Written by John Berry on 6th July 2017. Revised 13th July 2019.

10 min read

Entrepreneurs dream up wacky ways of doing business.

One entrepreneur wanted to act as an intermediary between workers undertaking cleaning activities at various private houses. The entrepreneur was disinclined to employ the cleaners but still wanted to have a margin on their efforts. And if a cleaner couldn’t go to a house one day, the entrepreneur would want to supply a substitute.

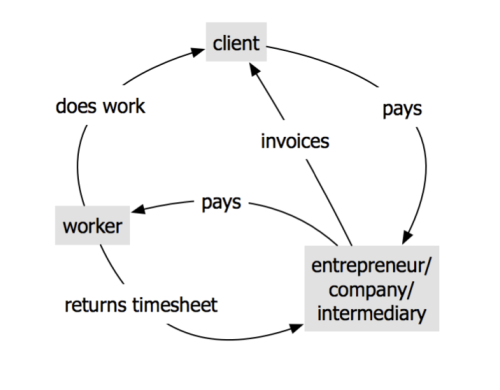

The situation is shown diagrammatically illustrating who pays who for what.

By any analysis, there’s no way for the entrepreneur to avoid becoming the employer.

But yet many entrepreneurs behave as intermediaries between client and worker – therefore it must be possible without becoming the employer. So how do such arrangements arise and how ‘legal’ are they?

Entrepreneurs and Companies

Much is explained by analysing the relationships between the parties, understanding whether the contracts between them are ‘for services’ or ‘of service’.

Companies exist because they are the most efficient way of an entrepreneur gaining the services of others. Most entrepreneurs start with their own effort, swiftly augmenting their effort with that of others with whom they build a relationship. Those others are not employees – that comes later.

As the entrepreneur’s business grows, there comes point when the transactional costs of managing those others at arms’ length becomes high and the contractual relationship is modified. Those others ‘come indoors’ under the entrepreneur’s ‘roof’ and they become employees.

This makes it sound as if it is all one way – from outside to in – with those others becoming employees. As the UK economic situation has evolved, the ‘employment’ situation has become more complex. And arguably as it evolves further, gaining services of others will increase again in complexity. It’s likely that in the future we’ll see a very flexible contractual arrangement evolve.

This blog aims to elaborate on the simple case in the introduction to provide a complete understanding of the possible relationships between entrepreneurs and their companies and workers.

The Concentric Model of Control

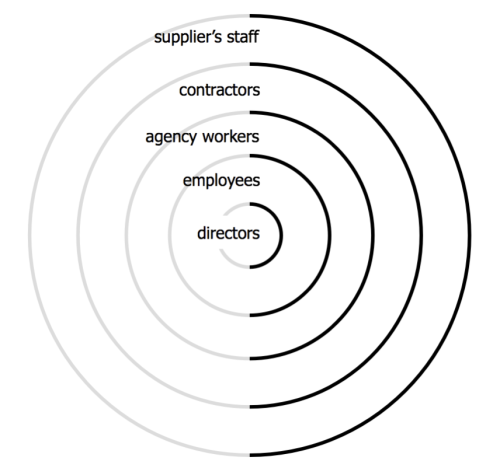

One way of looking at the relationship between an entrepreneur and those who serve him or her is to consider  the relationships as a series of concentric circles. At the heart is the entrepreneur and with him or her a number of directors trusted with the prosperity of the company. Distance from the centre represents the degree of control that the directors can expect over the four worker types and their work.

the relationships as a series of concentric circles. At the heart is the entrepreneur and with him or her a number of directors trusted with the prosperity of the company. Distance from the centre represents the degree of control that the directors can expect over the four worker types and their work.

UK statute gives significant control to directors over their employees. Employees ‘come indoors’ and submit to the instructions of the directors in return for a regular wage. The term ‘employee’ describes a worker who has a close relationship between them and the firm or ‘employer’. Those employees are under a contract of service.

No other worker type has such a close relationship. No other worker is an employee of his or her ‘client’. The directors have no direct control over any other worker type – nor do they automatically benefit from rights to their intellectual property nor can they automatically expect their confidentiality.

The model then shows others in order of decreasing relative control by the directors, from contractors out to the employees of supplier companies. And as control is lessened, the contracts typically move from contracts ‘of service’ to become contracts ‘for services’.

Contracts as an Attempt to Define the Relationship

Many directors, workers and sub-contractors attempt to define the rights and obligations of the parties by writing and signing a contract. This has some weight but is not the defining criterion – third parties like the HMRC will look at how the parties behave rather than what they have written.

A study of the contractual relationships is therefore essential to further understand the simple model built above.

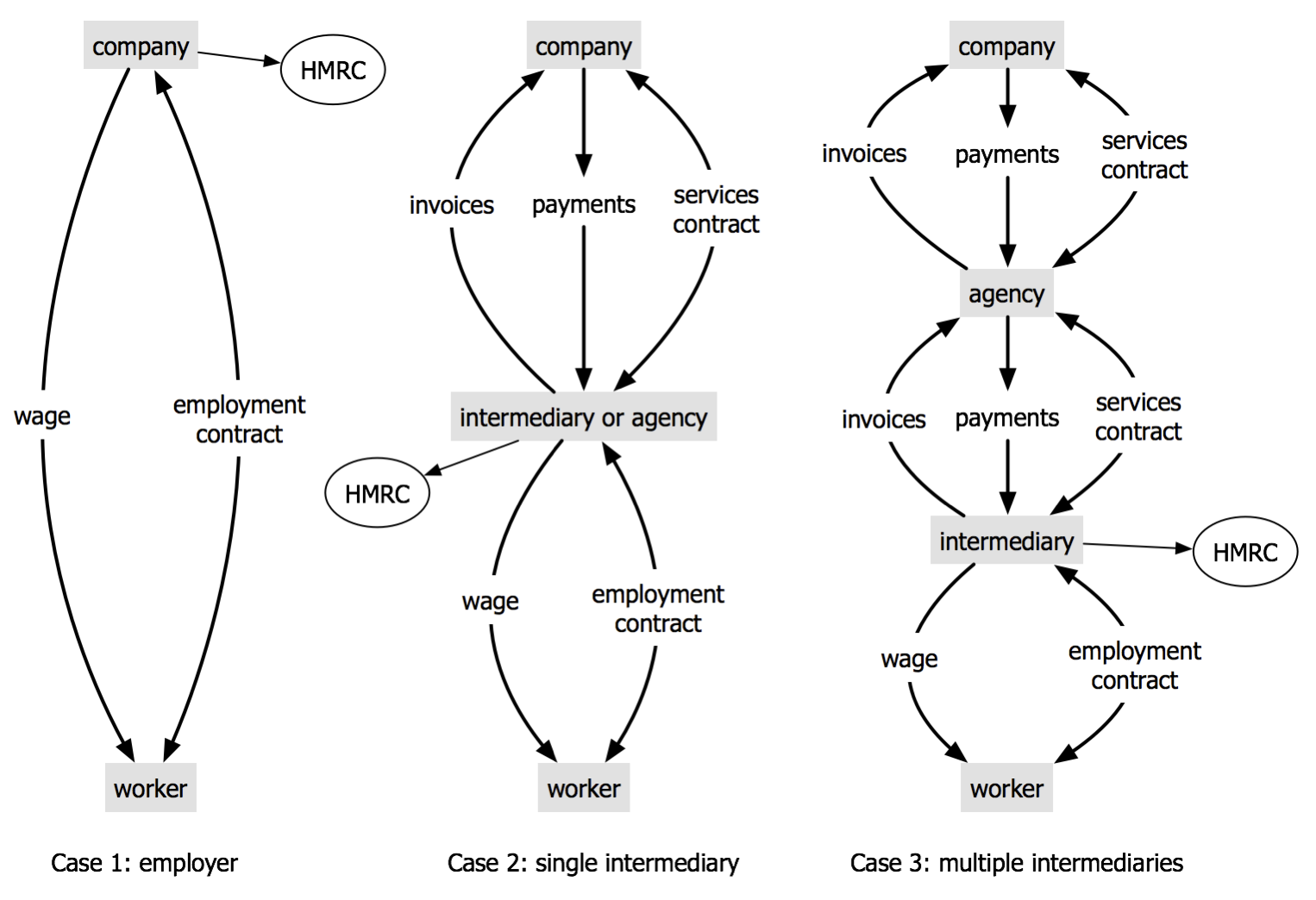

By far the simplest contractual arrangement is that in Case 1 between employer (company) and employee.

The employer offers an employment contract and the employee signs it to signal that he or she accepts its terms. In reality there is much that defines the employment contract that is laid down in statute. For example, the Employment Rights Act 1996 states that an employer can expect that the employee will hold all information about the employer confidential. And the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988 says that the employer has the right to any intellectual property created in the course of the employment.

As we move from the employee ring of the concentric model, we see an intermediary appear in the relationship, buffering the company from the worker. This is the desired role of the entrepreneur in the introduction, now shown in Case 2.

There are perhaps three types of intermediary before we reach the outer ring.

Defining Intermediaries

Firstly, many workers are disinclined to seek work direct with a company and prefer to go via an employment agency. The agency seeks to reach an agreement for supply of services, or a business-to-business agreement, with the company for the provision of work. It then recruits a number of ‘agency workers’ to its staff corps and supplies these workers ad hoc to the company. This often suits the company because it only needs labour from time to time and wants to be able to disengage from using the labour at a whim.

In this instance, the agency employs the worker and the relationship between agency and worker is that of employer and employee. There is no escape: the entrepreneur as intermediary must accept its employer’s obligations.

Whether such an arrangement suits the worker is a moot point. It perhaps depends on whether the worker only gets paid when actually working or if they have a contract that pays between assignments.

The agency then deploys the workers, invoicing the company for the effort and paying wages to its worker employees.

Adding Complexity to the Agency Case

Secondly, something like seven million workers in the UK are employed by their own company.

Some elect to gain limited liability and form a company that reports its status from time to time to Companies House. Limited liability simply means that the owners of the company are, generally, not personally liable for the debts of the company. Others elect not to seek limited liability and trade as self-employed or as a sole-trader. ‘Self-employed’ and ‘sole-trader’ are the same thing.

In both the limited liability company and sold-trader/self-employed cases, the intermediary is the worker’s own company in which he or she has significant interest.

The contractual situation is the same as the employer-employee case – though often there is no employment contract between intermediary and worker since this makes no sense given that worker and owner/director are the same person.

The contractual situation is the same as the employer-employee case – though often there is no employment contract between intermediary and worker since this makes no sense given that worker and owner/director are the same person.

Typically such workers are referred to as ‘contractors’.

The scenario here should not be confused with the supplier case. In the contractor case, the contractors are employed in their own company simply to facilitate an easy relationship with their client, the company with which they enter a business-to-business contract. Generally they only work for that company and no other, at least for a period of months if not years.

Supplier’s Workers

Finally, many companies contract under a contract ‘for services’ with other companies for the supply of goods and services that they themselves do not have.

In this case, the company enters a business-to-business agreement for supply with a supplying company. This supplier then employs workers. Those workers may then work with the client company – but critically, they do not come under the client director’s direct control. And the business-to-business agreement sets out the required deliverables.

Generally, such business-to-business agreements define performance independent of who in the supplier actually does the work. Indeed, generally they have no say over who does the work. Issues like intellectual property ownership and confidentiality are handled in the business-to-business contract.

The supplier’s employees would then be under an employment contract with the supplier and the relationship is the same as described above between the client company and its employees.

Further Confusion

Sometimes, there are more entities in the chain!

It is possible that the client company will contract with an agency for the provision of labour, just as in the agency case above. The agency will then find a worker and contract with them via his or her own limited liability company or as a sole-trader or self-employed person.

The contractual arrangements are shown in the contractual figure above.

Tax and the Duck Test

Now, the big issue in the above relationships is where liability for payment of tax lies.

There are two tax types in the UK – income tax and social tax or National Insurance payments, both based on the size of a worker’s wage.

The UK has a mature system of tax recovery where the employer collects the tax owed by its employees and pays this to the HMRC. This relies of course on identifying where the employer-employee relationship is located in the overall series of relationships – and hence who the employer is.

Despite the tax recovery system being quite effective, many workers have endeavoured to avoid paying tax. A number of questions have been developed by the HMRC to determine if the worker is employed, is an agency worker or is self-employed. These are fine but in the end, the status is only really determined by observation of worker behaviour.

Though nothing to do with the HMRC, the duck test applies. It’s called a duck test because one can suggest that “if it looks like a duck, swims like a duck, and quacks like a duck, then it probably is a duck”. It’s an example of abductive reasoning – a conclusion is reach by applying logic to what’s observed.

The duck test applied to the complex contractual relationships discussed here allows inference about who employs the worker. Questions are used about, for example, whether the worker is supervised, whether tools are provided and whether the worker goes into a set place each day to carry out the work. If this test suggests they are an employee, their employer is then liable to collect tax from them on behalf of HMRC.

This liability for tax collection is indicated on the relationships diagrams above by an arrow out from the employer to ‘HMRC’.

Making it Work

One thing not mentioned in the introduction was that the market price that the client was prepared to pay for the cleaning services was fixed.

Two issues then occur.

When a company invoices a client, they would be expected to charge Value Added Tax (VAT). Because the end client in the introduction is a private individual who cannot claim back VAT from the HMRC, this simply subtracts from the market price to reveal the company’s selling price.

In addition, the reason the company is playing in the market is to earn profit for its shareholders. For every intermediary a margin must be added – and the more intermediaries, the more the worker’s wages are squeezed by those margins.

In fact, in the case described in the introduction, the market price could not allow anything other than employment illustrated by Case 1. As soon as an intermediary appeared and VAT was paid, the market price minus workers’ wages exceeded the available selling price including the intermediary’s margin. The margin was too small and the business not viable.

And however it’s described, the cleaners are behaving as the entrepreneur’s employees and so HMRC would pursue the entrepreneur for VAT, income tax and National Insurance.

There’s no escape – no way round – no way to avoid the simple logic that determines that the entrepreneur, acting as an agency[1], is the employer.

- An agency acting in this way is governed by the Agency Workers Regulations 2010.