Winning employee commitment by granting idiosyncratic employment deals

Winning employee commitment by granting idiosyncratic employment deals

Written by John Berry on 21st October 2017. Revised 30th October 2017.

32 min read

If managers can get all staff to be committed, other management and leadership activities become possible. Without committed staff, there’s little the manager can do to achieve goals and the firm will just drift.

If managers can get all staff to be committed, other management and leadership activities become possible. Without committed staff, there’s little the manager can do to achieve goals and the firm will just drift.

Commitment and its causes is a topic of academic study too. If the causes of commitment can be understood, academics can help managers understand what to do to drive commitment. Academics study commitment because these causes are not clear and hence it’s not clear what managers should do.

This paper describes commitment and outlines research that shows what managers can do to achieve commitment.

Readers specifically interested in the past work and the research conducted should read the whole paper. For managers who just want an overview, read the Introduction, Background and Discussion and then the Implications and Further Work at the end.

Introduction

Previous researchers have established relationships between forms of idiosyncratic employment deal (i-deal) and employee affective commitment. In the academic press, the way i-deals and affective commitment are described and the relationship between those two variables is reasonably well established.

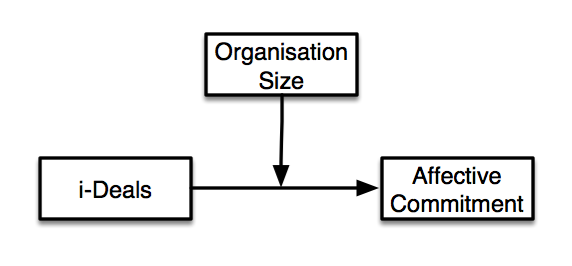

Previous work has however been unconcerned about the size of organisation in which the relationship exists and has ignored any possible effects that organisation size may have on the relationship.

This paper reviews past empirical research and theoretical underpinning. It describes new research competed by TimelessTime that corroborates previous work but specifically categorises organisation size, collecting data from employees working in micro, small, medium and large organisations in the UK. Using Blau’s social exchange theory, this research initially speculated that the relationship between i-deals and employee affective commitment would be stronger in small organisations than in large.

Using data from a sample of 103 professionals and managers, the results from this study suggest that the converse is true: that the relationship between what are termed ‘task and work responsibilities i-deals’ and employee affective commitment is strongest in large organisations. This means that whilst managers in smaller firms can exploit the relationship between i-deals and affective commitment, they will have to work harder to gain the same benefit compared to colleagues in large organisations.

Whilst rooted in the social exchange theory, this study speculates that self-development may be a more relevant theory for understanding this unexpected result. This lays the way for others to theorise on why this should be so and test further the findings.

Background

The concept of a contract between organisation and individual has existed ever since one employed the other to do work.

Managers bring the employment contract to life in the workplace through what has universally been described as the practices of human resource management (HRM)[1][2]. If managers can understand and implement effective human resource practices, improved business outcomes follow[3]. By defining and enhancing the relationship between employer and employee, the employment contract is something that enhances organisation outcomes such as turnover, profit and effectiveness[4].

Managers do however have significant flexibility about what elements to include in the employment contract[5]. In large organisations they are aided by in-house human resource management professionals whereas, in small organisations, managers rely on external consultants such as TimelessTime, and their own training and experience[6].

But research suggests that in small organisations, managers don’t conceptualise a link between organisational outcomes and their competence in human resource management in the same way as managers in large organisations. This is possibly as a result of their poor human resource management skills and knowledge in those small firms.

This ‘problem’ with human resource management in small organisations is not helped by lack of research in the sector. Many suggest that the small organisations sector (employing about 40% of the UK workforce[7]) has generally been ignored by researchers to date.

The argument so far suggests that small and large organisations are different, using different practices to reify the employment contract. The lack of research into human resource management in small organisations also suggests there is work to be done to better understand these differences and aid small organisation managers to achieve better results.

Discussion

Continuing the discussion on outcomes, if outcomes are positive at a personal level for each employee, the desired operational outcomes (like quality and productivity) will be achieved. If all other things are equal, the organisation’s desired business outcomes will also be realised. So it is for the manager in both small and large organisations to do what’s needed at the individual level to cause the cascade from a plurality of individual effects to corporate result.

Since different human resource practices affect outcomes in different people in different ways, the issue then is what managers should choose to do.

Practices invoked by managers influence the beliefs, attitudes, feelings and behaviours of their employees and these are key in realising positive personal outcomes[8].

One key desirable outcome is the mental state of commitment.

The outcomes for an employee feeling committed to their firm are low intention to quit, enhanced self-esteem and enthusiasm to take on additional tasks[9]. Managers must have their workforce committed in order to best realise operational outcomes[10].

So commitment is desirable and can be achieved by selective application of human resource management practices. But because humans are individual, with unique personal characteristics, and because human resource practices realise different outcomes in each employee, the implication is that those human resource management practices should be idiosyncratic, unique to each individual. To describe these idiosyncratic practices and contracts, researchers have coined the term ‘i-deal’[11].

This paper seeks firstly to confirm the relationship between i-deals and commitment and second to explore how the relationship differs between large and small organisation types.

Given that there is a lack of research into human resource management practices in small organisations, this research will add to the HRM body of knowledge in this sector. It will also give managers in both large and small organisations some useful guidance about how idiosyncratic elements of the employment contract influences desirable mental states in employees.

What’s an i-deal?

An i-deal is a concession granted by a manager in return for an employee’s commitment. The action of grant and return is a form of exchange of valuable assets[12]. An employee’s reaction to that stimulus depends on how highly they value what they are given.

Such exchange can be transactional and economic, concerning perhaps pay, or it can be relational and psychological and concern the granting perhaps of additional responsibilities. Generally transactional exchange occurs prior to the employee joining the organisation. Relational exchange on the other hand can be negotiated and re-negotiated many times within an employee’s career. Relational exchange will tap implicit motives whilst transactional exchange will tap explicit. For i-deals to influence commitment, the i-deal must have implicit meaning and value[13].

Organisations try to standardise their employment contracts. Structural constraints such as bureaucracy also limit managers’ flexibility and hence ability to grant i-deals. In large (and perhaps bureaucratic and inflexible) organisations, therefore, there is a logical implication that i-deals are likely to be rare and rareness increases their value.

For maximum value, it should be the employee that asks for the concession and not the manager who offers. When an i-deal is granted following such request, the organisation is sending a signal of the employee’s value. To further inflate the value of the i-deal, the employee needs also to be convinced that it is not only unique within his present organisation but would likely not be available in others to which the employee might apply for work[14].

So the i-deal asked for and granted should focus on tapping intrinsic motives. Researchers have proposed different i-deal factors. Some propose using flexibility- and development-centred i-deals. Others used i-deals centred on workload reduction. Finally a third group proposed i-deals based on tasks done or responsibilities. A study of these factors shows common ground: development may involve training but more often it involves granting of added responsibilities to stretch competency. In line with decisions made by Rosen et al, this paper centres on a single factor termed the task and work responsibilities i-deal.

Task and work responsibilities i-deals are therefore conceptualised here as request-grant exchanges between employee and manager for idiosyncratic variation to a contract of employment associated with desired change in task and work responsibilities. The value of the exchange for the employee is a belief that the task and work responsibilities i-deal is unique within the employing organisation and would not be available from future employers either. Task and work responsibilities i-deals are measured by their presence and strength as a single variable.

Explaining commitment

In this study, commitment is regarded as a psychological state existing within an employee that causes them to attach to their organisation[15] and make open or private promises to continue to provide their labour for the benefit of the organisation. By attaching to and intending to stay with the organisation, the employee makes other management intervention possible and this in turn influences performance. There is therefore some link between commitment to the organisation and performance both immediately and into the future. And for managers, performance is arguably a highly desirable individual outcome.

Porter et al[16] and others focussed on commitment to the organisation as an entity. Several researchers have attempted to de-construct organisational commitment into constituent parts. Meyer et al consider organisational commitment to be formed of three factors: affective, continuance and normative commitment. Under affective commitment, an employee wants to stay. Under continuance commitment, they need to stay. And under normative commitment they are obliged to stay. These factors comprise the Mayer three-component model (TCM).

Liu et al describe work as a source of meaning in an employee’s life. Meaning is an affective concept. They suggest that in order to derive meaning from manager-employee exchanges such as i-deals, one must seek benefits beyond simple economic exchange, tapping affective and intrinsic characteristics.

Evidence from prior studies also supports the link between HRM practices and affective commitment and between affective commitment and the intention to quit. In order to centre on meaning and relational exchange and to utilise these prior studies, this present work therefore adopts the TCM approach to commitment, focussing specifically on affective commitment.

Use of affective commitment allows a useful link to be investigated between HRM practices (such as the use of i-deals) and operational outcomes (such as staff turnover), hence adding to the understanding of HRM practices in both large and small organisations.

About organisations

Organisations comprise owners, managers and employees. In a small organisation of a few 10s of employees (and in particular, in small commercial firms) owners often manage and as a result it is difficult to perceive an organisation separate from the owner manager. In a large organisation of several thousand employees, managers, formed in a hierarchy, act as agents for owners whilst themselves being employees. Arguably, large organisations seek to standardise and de-personalise organisation-employee relations whilst in small organisations, those relations are close up and personal.

These arguments imply that the employment contract will be made real in different ways in different sizes of organisation. It is likely therefore that i-deals, as a tool for making the contract live, will have a different effect on employees in different sizes of organisation. It’s essential therefore that organisation size is considered a variable in the relationship between task and work responsibilities i-deals and employee affective commitment.

The European Commission has played a central part in standardising size-of-organisation definitions[17]. It defines four size bands: micro – <10 employees, small – <50 employees, medium – <250 employees leaving large as 250 and above employees. The EU definition was developed to aid distribution of Structural Fund monies.

Most micro-organisations are led by an owner-manager with informal organisation-employee relations. As the organisation grows, so relations formalise though it is only when an organisation becomes what the EU call ‘medium’ sized that hierarchical structures based on departments emerge and employee relations standardise[18]. And it is only on reaching over 250 employees that HRM as a discipline is discernable.

Whilst other size categories are possible, none are so well accepted and pervasive. This study therefore uses the EU categorisation.

Various researchers and writers suggested that “research on i-deals is in its infancy” and that there has been patchy work done. Much is rooted in Rousseau’s work on psychological contracts.

Past research

Rousseau, Hornung and Kim reported a moderate positive relationship between the instance of developmental i-deals and a social exchange variable (r = 0.31, p<0.01). Liu et al showed moderate positive correlation between development i-deals and affective commitment (r = 0.24, p<0.01) whilst Rosen et al showed a slightly stronger relationship between a better-defined variable of task and work responsibility i-deals and affective commitment (r = 0.3, p<0.001). Hornung et al[19] suggested weak positive relationships between development i-deals and performance (r = 0.2, p<0.01) and between development i-deals and motivation (r = 0.14, p<0.05).

This latter work needs some care in interpretation considering the distinction between commitment and motivation variables. Possibly the study indicating the strongest correlation is that that after Ng and Feldman[20] reporting r = 0.46 and p<0.01. They used variables of contract idiosyncrasy and affective organisational commitment.

This latter work needs some care in interpretation considering the distinction between commitment and motivation variables. Possibly the study indicating the strongest correlation is that that after Ng and Feldman[20] reporting r = 0.46 and p<0.01. They used variables of contract idiosyncrasy and affective organisational commitment.

These past works illustrate generally that one would expect a moderate positive relationship between developmental i-deals and affective commitment in organisation-employee relationships.

By studying a large organisation of 20,000 employees sub-divided into units and groups, Hornung et al were able to look at how size intervened in the granting of i-deals. They found that unit size and group size correlated negatively with incidence of flexibility i-deals suggesting that it was easier to put i-deals in place in smaller groups and units.

The correlation result between size and developmental i-deals was however weak and non-significant suggesting perhaps that development was more centralised, rendering the manager-employee exchange relationship less relevant.

Overall, there has been an unstructured approach in previous work to selection of participants, variables and methods and it’s no surprise that Liu et al appeal for a standardisation of research to grow knowledge on the subject.

What theory tells us

Blau[21] illustrates how the relationship between two individuals, such as manager and employee, can be described by his theory of social exchange.

He describes how most human pleasures have their roots in social life. This suggests that for a manager to gain, he or she must engage with their employees. The question therefore is what course of social interaction is best for both parties?

For social interaction to take place, Blau says social attraction must be present. The parties to the interaction must find one another to have impressive qualities. Those impressive qualities result in the relationship providing rewards. And the promise of future rewards sustains the relationship.

Homans[22] conceptualised social relations as an exchange of activity between two people that is in some way rewarding. He noted that this exchange exists throughout social life (and as an organised form of social life, this would extend to the work environment). Blau extended this to say that “an individual who supplies rewarding services to another obligates him”. To discharge this obligation requires the obligated person to do something for the other at some future point in time.

Blau extends his theory of social exchange to suggest that it involves voluntary actions of the participants. Whilst the first recipient is obligated, they are motivated to respond only though further expectations of reward and the desire to sustain the relationship.

Social exchange relies on one person doing the other a favour with the expectation of a return of favour some time in the future. The key thing is that the future favour is not defined. In the present study the initial favour is the granting of an i-deal with the expectation of future positive attitude (that results in affective commitment) from the employee. But that future positive attitude and the resulting affective commitment is not expressed.

Since social exchange is enacted by people and people are described by individual characteristics, a variety of conditions affect the exact nature of the relationship.

Blau notes that for every relationship forged between two people, other possible relationships have remained undeveloped. This illustrates the special value in a particular social exchange. The parties will have forgone other relationships that might have cost less and given more.

This emphasis on individual characteristics means that the social setting in which the exchange is developed is also significant. There are two aspects highlighted by Blau.

Firstly, the ability to enter social relations and the rewarding services provided is conditioned by the social position of the parties. Secondly, any single exchange relationship exists within a plethora of other exchange relationships experienced by all parties.

Social exchange exists within a plurality of pairs of social exchanges entered into by all parties, the numbers and strength of which depends on the complexity and size of the society.

The problem is however that as rewards come to be expected, they will also be taken for granted. Reference standards become established and certain groups within the society come to expect certain normal exchange behaviour between members. Conversely, new and unusual exchange relations are highly regarded simply because they have no such norms.

Social exchange theory assumes that individuals engaging in exchange have free choice and can reallocate their resources as they see fit in order to maximise their pleasure. This reallocation relies on the parties having full information about all alternatives. In the manager-employee relationship, managers would need to know which employees to invest in whilst employees would need to know all managers likely to provide the rewards they desire, including managers in other organisations.

Hypotheses

Perfect information is impractical and this imperfection distorts the system. The parties also have choice about who to enter exchange relations with. This choice means that participants will seek those with particularly impressive qualities. This results in competition for attractive partners who can yield desirable rewards at acceptable cost.

The number of partners is also constrained by the society size. Ideally, for perfect competition, a large homogenous population is needed. This indicates that in small organisations, there is a real limit as to the number and nature of social exchange relations that can exist. In larger organisations, greater choice is possible.

Overall, Blau’s social exchange theory suggests that the manager obligates the employee by granting them a task and work responsibilities i-deal. That obligation does not specify what will be given in return or when it will be given. The manager hopes that it will give them what they want from the employee – positive attitudes and behaviours. Those positive attitudes and behaviours are also not specified and the manager can only hope that they include positive affective commitment towards the organisation.

Overall, Blau’s social exchange theory suggests that the manager obligates the employee by granting them a task and work responsibilities i-deal. That obligation does not specify what will be given in return or when it will be given. The manager hopes that it will give them what they want from the employee – positive attitudes and behaviours. Those positive attitudes and behaviours are also not specified and the manager can only hope that they include positive affective commitment towards the organisation.

Research of this kind follows a prescribed lifecycle. Theory is used to develop hypothesis or claims. Investigation using questionnaires and the like then provides evidence to support or refute these claims.

Blau’s theory leads to the first of the hypotheses: that there is a positive relationship between the granting of a task and work responsibilities i-deal and employee affective commitment.

Blau suggests that context is key to social exchange function. He suggests that for social exchange to work, the players must have the ability to develop a large number of exchanges. This suggests that the relationship between i-deals and affective commitment should be strongest in large organisations.

Managers act as the primary interface between organisation and employee. But managers in small commercial organisations are typically also the owner. As owner manager they will arguably have the executive power needed to grant i-deals.

There are two primary styles of large organisation. On the one hand large organisations are sub-divided into units and groups with the organisation mimicking a plethora of connected small organisations. On the other, managers and employees are in multiple dyadic relationships with each employee getting supervision of some aspect of their employment from different managers.

This latter case resembles a network structure. In both styles, hierarchy and diffusion of power mixed with organisational policy make it difficult to establish who has the executive power to agree to i-deals. In the small organisation the dyadic relationship arguably has clarity. In the large organisation it exhibits confusion.

Conceivably therefore, it ought to be easier to set up i-deals between manager and employee in small organisations. This leads to the third hypothesis: that the granting of task and work responsibilities i-deals is more prevalent in small organisations.

The argument above suggests that social exchange exists between manager and employee. They build trust through successful exchange of valuable commodities. Blau suggests that the social attraction needed for exchange can only be built through familiarity: it’s difficult for an employee to build a relationship with a distant or absent manager or where the relationship strength is diffused across several managers.

Logically therefore social exchange should be more successful when the target manager is known and worked with daily. This leads to the final hypothesis: that when task and work responsibilities i-deals are granted in small organisations, the effect on employee affective commitment is higher than in large firms.

The present research

The aim of the present study is to determine if organisation size matters in the relationship between the granting of task and work responsibilities i-deals by a manager and the experiencing of affective commitment in employees. This requires a sample across many organisations categorised as micro, small, medium and large with roughly equal numbers of respondents in each.

Some researchers (for example, Hornung et al) note that idiosyncratic deals are always specific to the organisation context, hence many respondents within any sample from the same organisation will likely give similar outcomes and hence cause a distortion.

Sample polled

A list of 644 LinkedIn contacts was readily available to the author. Around 30% of these were not employees – they were self employed, unemployed or retired. Around 40% were non-UK nationals or UK-nationals working abroad. To include non-UK nationals and those working under non-UK employment arrangements would have demanded consideration of different cultures in the employment relationship. Whilst culture would be an interesting extension of the present project, these data were excluded in search of reduced complexity.

The final on-line questionnaire was sent to 170 people. Six were employed by one organisation. No other organisation had more than 3 possible respondents. Of the 170, 108 people responded and 103 completed the survey and gave useful data. The responses were received between February and May 2014.

Of the 103-employee sample 62% were male and 38% female. The mean age category was 41-50 years. All were in professional/managerial jobs. The mean tenure was in the category 3-10 years.

The i-deals scale

Rousseau & Kim developed a scale based on interviews about the types of i-deals negotiated. They developed three dimensions of i-deals: work flexibility, reduction in workload and career development opportunities. Since this present study seeks to investigate the link between i-deals and affective commitment, the interest here is on career development.

Logically therefore this study could simply ask questions about the degree to which managers have agreed to develop staff and this would tend to focus on training. A well-established principle however in staff development is the granting of work that is, by its nature, developmental.

This widening of the scope of ‘development’ better accommodates the idea that in small organisations, there is often little training being done but there is certainly much development as employees move to handle a wider range of unique duties. Change in job done as a form of development adds job design to the definition. Developmental opportunities can also come from taking on increased responsibility, taking ownership and accountability for action and learning from this.

Rolling these developmental ideas into one supports the use of a single measure covering “task and work responsibilities” to describe negotiations around “what an employee does on the job”.

The present study employed this developed i-deals measure after Rosen et al.

This measure involved seeking responses on a five-point Likert scale indicating the degree to which each of six statements apply. Examples of these statements include ‘I have successfully asked for extra responsibilities that take advantage of the skills that I bring to the job’ and ‘in response to my distinctive contributions, my supervisor has granted me more flexibility in how I complete my job’.

The final value of each measure for each respondent was arrived at by averaging the six scores.

The commitment scale

Factor analysis of the affective commitment scale has illustrated that the three components of the TCM measure distinct constructs. The component of interest to the present study is affective commitment.

The affective commitment was assessed using responses to six questions, for example ‘I feel as if this organisation’s problems are my own’ and ‘I do not feel a strong sense of “belonging” to my organisation’. Respondents were asked to indicate answers on a scale from ‘strongly disagree’ to ‘strongly agree’.

The final measure for each respondent was arrived at by averaging the six discrete Likert-scale values.

Organisation size

Use of the EU definitions of organisation size failed to reveal useful results. Correlation and regression analyses on the survey data showed that there was a significant effect in the large organisation category. Tests of each of the smaller sets – for micro, small and medium sized organisations – were completed to investigate effects in each category. No significant effects were found. The resulting data set had too few data in each of the three smaller organisational size categories (N=17, 23 and 18 respectively).

Use of the EU definitions of organisation size failed to reveal useful results. Correlation and regression analyses on the survey data showed that there was a significant effect in the large organisation category. Tests of each of the smaller sets – for micro, small and medium sized organisations – were completed to investigate effects in each category. No significant effects were found. The resulting data set had too few data in each of the three smaller organisational size categories (N=17, 23 and 18 respectively).

To make sense of the data it was therefore necessary to aggregate to create a super-set for comparison with the effect in the large organisation category. Further tests were done in search of effects for combinations of the categories. A single statistically significant effect was found by combining the micro, small and medium categorical data.

Re-coding of the organisational size variable allowed further investigation of two sets (N = 58, N = 45), one for a new category of small organisation and the other for the original large organisation category. A small organisation was therefore re-defined as one with less than 250 employees whilst a large organisation is one with more than 250 and this has also been used below. Places where the original 4-category and the new 2-category organisational size variables have been used are indicated.

Results

Four forms of analysis were completed in pursuit of evidence to support hypotheses. Correlation was done to investigate relationships between the variables. A t-test was completed to investigate the difference in means between the two categories of organisation size. Multiple regression was used to focus on one pair of variables, controlling for others. Finally the data was re-coded and split and multiple regression was done on constructed moderator variables to investigate moderation effects.

These analyses are explained in turn.

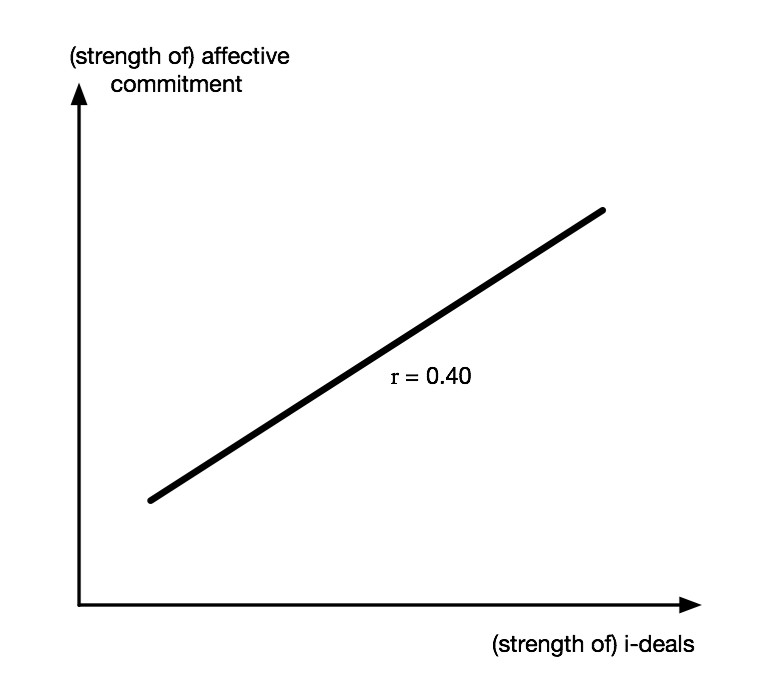

The first significant correlation is that between task and work responsibilities i-deals and affective commitment (r = 0.40, p = 0.000). This suggests that the granting of i-deals does have a moderate effect on engendering a feeling of affective commitment in employees. Tenure is also related to affective commitment (r = 0.292, p = 0.003). Affective commitment increases with increasing tenure with the organisation.

This study is particularly interested in the effect that organisation size has on the relationship between task and work responsibilities i-deals and affective commitment. The relationship between i-deals and organisation size shows no statistical significance.

However, there is a moderate effect and negative relationship between organisation size and affective commitment (r = -0.263, p = 0.007) suggesting that affective commitment is greater in smaller organisations than in large.

The third hypothesis posits that task and work responsibilities i-deals are more prevalent in small organisations than in large.

To explore the third hypothesis, a t-test was done with the revised dataset (small N=58, large N=45), comparing the means of the task and work responsibilities variable between the two sub-sets using a split file. The difference in means at the 95% confidence level was 0.2 with the mean in small organisations slightly higher than in large organisations but the result was non-significant. Non-significant results nullify the analysis: the granting of task and work responsibilities is no more or no less prevalent in small organisations than in large.

Since the relationship between task and work responsibilities i-deals and affective commitment may be made up of several interacting variables, a multiple regression was conducted to isolate the central relationship proposed in the first hypothesis.

In this regression, controlling for objective age, tenure and organisation size shows a moderate isolated effect size linking task and work responsibilities i-deals and affective commitment that is also statistically significant (β = 0.34, p = 0.000). These other effects do modify the relationship but there is still a moderate positive relationship when all are controlled for.

The data was analysed to find the effect for small organisations and the data re-coded to give two sub-sets, one for small organisations (N=58) and the other for large organisation (N=45). The correlation for this is 0.281 for small organisations and 0.491 for large. Both are statistically significant.

This correlation suggests that in both small and large organisations there is a statistically significant relationship between task and work responsibilities i-deals and affective commitment. In large organisations, however, there is a significantly greater effect than in small. This means that in large organisations, managers benefit from having to put less effort in to the granting of task and work responsibilities than do their colleagues in small and medium sized organisations.

Appropriateness of method

Specific predictor, criterion and moderator variables were selected based on social exchange theory and past research. The unit of analysis was the employee.

The use of a questionnaire was in line with past research. The variables and their item design made use of previous work and this fitted with calls by previous researchers for standardisation. Use of previously developed items means that this research builds on past peer-reviewed work. A single questionnaire took a cross sectional sample at one point in time. The use of a questionnaire was expedient, permitting the researcher to be isolated from the data gathering. This isolation avoided researcher-introduced bias and ethical conflict.

The captured data was analysed using IBM SPSS v20 and analysis focussed on correlation, regression and descriptive statistics to develop support for four hypotheses. The data represented a sample of a population with inference made from sample to population with associated confidence. The sample N was 103.

Discussion on results

The moderate positive correlation linking task and work responsibilities i-deals and affective commitment (r = 0.4, p = 0.000) suggests that there is support for the first hypothesis: that there is a positive relationship between the granting of task and work responsibilities i-deals and employee affective commitment.

The multiple regression run to control for less interesting variables shows that once age, tenure and organisation size are controlled for, the relationship between i-deals and employee affective commitment weakens but remains moderate (β = 0.34, p = 0.000). This result is in line with those of previous research (for example Rosen et al reported r = 0.42, p <0.001).

The results also suggest that despite arguments made from social exchange theory, there is no significant difference in the incidence of task and work responsibilities i-deals in small and large organisations. The third hypothesis, that the granting of task and work responsibilities i-deals is more prevalent in small organisations, is not supported.

Considering that the sample means of task and work responsibilities are around 3.6 on a score of 1 to 5, and considering that there are few respondents in the samples that do not benefit at all from task and work responsibilities i-deals, previous statements by other researchers about the rarity of i-deals is not supported.

Previous researchers suggested that it is this rarity that enhances the value of i-deals and that it is this rarity that drives affective commitment. It seems very possible that social exchange theory may be less of an explanation that originally thought.

The correlation of the coded sub-sets of data for small (N = 58, r = 0.281, p = 0.032) and large (N = 45, r = 0.492, p = 0.001) organisations suggests that there is some explanation needed. A core attribute of the social exchange theory is value placed by the employee in the medium of exchange, in this case the i-deals granted.

Key conclusion

The theory holds that the greater the value in the exchange, the greater the outcome. The results here imply that there is some other characteristic that differentiates small and large organisations that gives rise to greater effect in large over small.

The key hypothesis, the fourth, that when task and work responsibilities i-deals are granted in small organisations, the effect on employee affective commitment is higher than in large organisations, is not supported – the result is the converse. It is in large organisations that the relationship between i-deals and affective commitment is stronger.

Implications and further work

Of major significance is the apparent inability of social exchange theory to provide the single explanation. The results suggest that it’s in larger organisations that the relationship between task and work responsibilities i-deals and affective commitment is strongest. This is counter to the earlier argument developed here from social exchange theory.

Liu et al considered a model in which organisation-based self-esteem moderates in the relationship between developmental i-deals and affective commitment. This does offer a possible explanation with self-enhancement theory a direction for future theorising. Perhaps in large organisations there is more scope for self-esteem stemming from task and work responsibilities i-deals than in small organisations.

Despite this, the work done here does add to the understanding of how to gain performance in staff. Performance is the most sought after factor in management. If staff are committed, they are more likely to stay with an organisation. Once committed, other management and leadership interventions can be used to achieve motivation.

The results in this and earlier studies arguably position the granting of i-deals as an essential part of a basket of measures that might be applied by managers to achieve motivation. Motivation is well established as an antecedent to performance.

The granting of i-deals is a simple concept for managers to work with. They need only let it be known that they are open to requests for i-deals. Assuming that staff are keen to enhance their capability, negotiations can begin. In principle this process can be turned into a heuristic for gaining commitment and potentially performance.

Psychologists work with theories and models; managers work with heuristics. If enhanced by further empirical work, this study has practical application to support heuristics.

References

[1] Jiang, K., Lepak, D., Hu, J., & Baer, J. (2012). How does human resource management influence organizational outcomes? A meta-analytic investigation of mediating mechanisms. Academy of Management Journal, 55(6), 1264–1294.

[2] Legge, K. (1995) Human resource management: rhetorics and realities, MacMillan Press, Basingstoke, UK, pp 96-138.

[3] MacMahon, J., and Murphy, E. (1999). Managerial Effectiveness in Small Enterprises: Implications for HRD, Journal of European Industrial Training, 23(1), 25–35.

[4] Castellano, W. G. (2009). A New Framework of Employee Engagement. Rutgers, the State University of New Jersey.

[5] Tsui, A. S., Pearce, J. L., Porter, L.W. and Triploi, A. M. (1997) Alternative approaches to the employee-organisation relationship: does investment in employees pay off? Academy of Management Journal, Vol. 40, No. 5.

[6] Learning and talent development review: annual survey report 2011. (2011). CIPD. Available at cipd.co.uk/learningandtalentdevelopmentsurvey accessed on 9th July 2014.

[7] Office for National Statistics ref. URN 10/92 13 October 2010, Statistical Press Release on the Small and Medium Sized Enterprise (SME) Statistics for UK and the Regions available at http://webarchive.nationalarchives.gov.uk/+/http://stats.bis.gov.uk/ed/sme/Stats_Press_release_2009.pdf and accessed on 13th July 2014.

[8] Takeuchi, R., Lepak, D. P., Wang, H., & Takeuchi, K. 2007. An empirical examination of the mechanisms mediating between high-performance work systems and the performance of Japanese organizations. Journal of Applied Psychology, 92: 1069–1083.

[9] Rousseau, D. M., & Kim, T. (2006) Ideosyncratic deals: How negotiating their own employment conditions affects workers’ relationships with an employer. Paper presented at the British Academy of Management, Oxford, UK, 2006.

[10] Castellano, W. G. (2009). A New Framework of Employee Engagement. Rutgers, the State University of New Jersey.

[11] Robinson, S. L., & Rousseau, D. M. 1994. Violating the psychological contract: Not the exception but the norm, Journal of Organizational Behaviour, 15: 245-259.

[12] Liu, J., Lee, C., Hui, C., Kwan, H. K., & Wu, L.-Z. (2013). Idiosyncratic deals and employee outcomes: The mediating roles of social exchange and self-enhancement and the moderating role of individualism. The Journal of Applied Psychology, 98(5), 832–40.

[13] Rousseau, D. M.; Hornung, S., Kim, T. G. (2009) Idiosyncratic deals: Testing propositions on timing, content, and the employment relationship. Journal of Vocational Behavior, Vol 74(3), Jun, 2009.

[14] Rosen, C. C., Slater, D. J., Chang, C.-H., & Johnson, R. E. (2011). Let’s Make a Deal: Development and Validation of the Ex Post I-Deals Scale. Journal of Management, 39(3), 709–742.

[15] Meyer, J. P., & Allen, N. J. (1991) A Three-component Conceptualization of Organisational Commitment, Human Resource Management Review, 1(1), 61-89.

[16] Porter, L.W., Steers, R.M., Mowday, R.T., & Boulian, R.V. (1974) Organisational commitment, job satisfaction and turnover amongst psychiatric technicians, Journal of Applied Psychology, 59: 603-609.

[17] The New SME Definition: User guide and model declaration, Enterprise and Industry Publications, European Commission, 2003, available at accessed on 12th July 2014.

[18] Achieving sustainable organisation performance through HR in SMEs, Research Insight report, Chartered Institute of Personnel and Development (pub.), 2012, available from http://www.cipd.co.uk/hr-resources/research/achieving-performance-hr-sme.aspx, accessed on 12th July 2014.

[19] Hornung, S., Rousseau, D. M., & Glaser, J. (2009). Why supervisors make idiosyncratic deals: antecedents and outcomes of i-deals from a managerial perspective. Journal of Managerial Psychology, 24(8), 738–764.

[20] Ng, T.W.H, & Feldman, D.C. (2010) Idiosyncratic deals and organizational commitment, Journal of Vocational Behavior, 76, 419-427.

[21] Blau, P.M. (1964) Exchange and Power in Social Life. New York: Wiley.

[22] Homans, G.C. (1961) Social Behavior, New York: Harcourt, Brace and World.