What HR data should I gather?

What HR data should I gather?

Written by John Berry on 13th July 2019. Revised 25th July 2019.

6 min read

When it comes to HR data, there is a wealth of it to be collected and analysed. HR data can be gathered from all the key HR activities like recruitment data, career progression data, personal development data, absence figures, productivity data, competency profiles and staff satisfaction data. Indeed, the saying “if you can’t measure it, you can’t manage it” arguably holds true - how can you decide what to do to improve absence levels, and therefore sickness-related costs, for example, if you have no clue what those absence levels are?

When it comes to HR data, there is a wealth of it to be collected and analysed. HR data can be gathered from all the key HR activities like recruitment data, career progression data, personal development data, absence figures, productivity data, competency profiles and staff satisfaction data. Indeed, the saying “if you can’t measure it, you can’t manage it” arguably holds true - how can you decide what to do to improve absence levels, and therefore sickness-related costs, for example, if you have no clue what those absence levels are?

And yet, just because you can measure it, does not mean you should. In over thirty years managing departments and firms, I’ve never once calculated absence. That’s not to say everyone was in rude health all the time. It was just that my continuous scanning and assessment of my people determined that absence was not a problem and the same is true of many management variables.

I’ve suggested that without data you can’t manage, but often that absence, and other such variables, do not need to be calculated. So, what is a manager to do here? With such a variety of variables to measure when it comes to HR data, what should you actually be measuring?

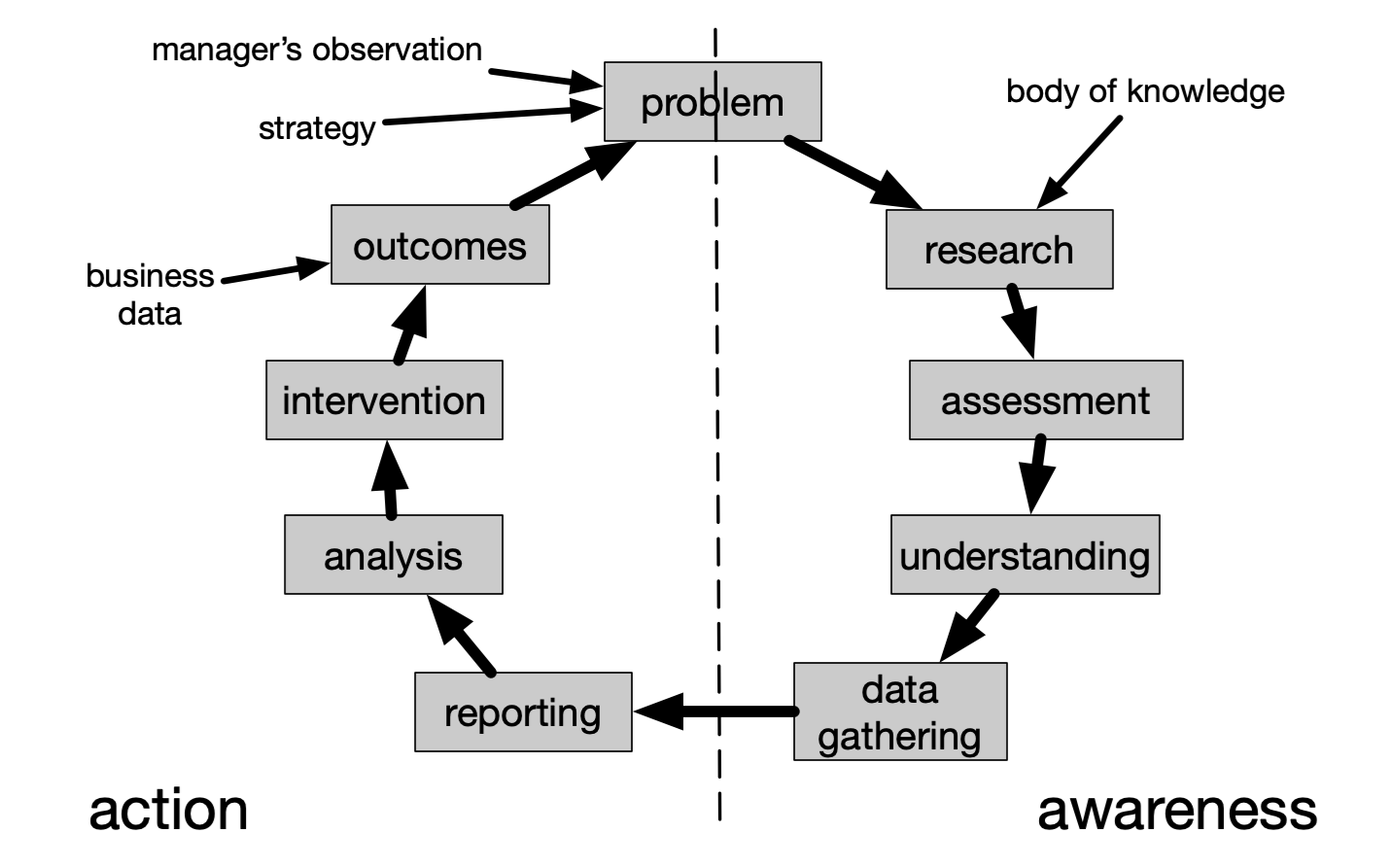

To answer this, we must first understand the difference between awareness and action when it comes to variables such as absence, engagement and wellbeing. Awareness is characterised as what we want to know, whereas action is all about reading the reports and deciding what to do. I’ve shown an illustration of the measurement cycle to show this point more clearly.

To start us off on our measurement cycle journey, and referring to the figure adjacent, we typically have a problem we are trying to address. This may come from a strategic statement (a variable that may be important to give the firm competitive advantage, for example) or a hunch that some HR variable (absence as a prime example) may be degrading. While it may be tempting at this point to jump straight to “lets gather some data, report it and make some conclusions” - I urge you to STOP RIGHT THERE. This generally only results in the wrong thing being measured and an unsatisfactory outcome to the whole process. “So, what am I meant to do instead,” I hear you say?

Let’s go through some key points together.

Firstly, and most importantly, please do consider the research that has already been conducted!

There is a wealth of data out there in academic texts and papers that cover decades of research resulting in a huge body of knowledge surrounding every conceivable management variable.

This point is so important because many managers are unclear about definitions – ‘engagement’ is a case in point. Many managers talk of employees being engaged with the firm whereas academics universally talk of commitment to the firm, but engagement with the job. I therefore ask you to begin all measurement activities with a bit of research into the variables and their characterisation. This will ensure you are measuring the right thing, and that the resulting data will allow you to make the correct management interventions.

Secondly, and once the right variables are agreed on, it’s time to think about the data that might be gathered. Before you get stuck into this, again please consider the huge body of knowledge on this.

DO NOT invent data. Instead, use established surveys and questionnaires to select data collection methods.

Collection of secondary data also saves considerable time and frustration. What is the point in setting up a brand-new data gathering exercise to merely replicate what you have in the system already? There is a place for primary data collection, but conducting a bit of research to work out what you have already (in manager’s day books and in electronic HR systems for example) is a no brainer at this point.

It is also worth noting here that a good manager should be able to second-guess the results and therefore perhaps minimise data gathering. Observations from weekly one-to-one meetings may, for example, allow the manager to assess whether commitment is an issue, and hence whether a formal study of this variable is needed.

And thirdly, we could now slide easily into the realms of over-zealous, overly academic statistical reporting – the sort of thing that we might criticise Government for. There is again a wealth of information out there covering statistics and reporting but I will cover some basics here.

To get a quick handle on your results, finding the average is not a bad place to start. Put simply, the average of your data set is the sum of the data divided by the number of data points. This might be helpful for looking at the difference in the average age of males and females in a firm, for example.

The difference between averages is also a popular report – and is used to report on the gender pay gap. Here the averages of two pay distributions, one for males and one for females, are compared to generate a single statistic.

Another useful thing to include is trend information. A trend tells us how the variable (like average age) has changed with time. When graphed, it is possible to also project into the future to give an idea of what may be – for example a trend indicating that average female age is increasing may, or may not, be useful (again consider just because you can, doesn’t mean you should).

Next we must consider error. Consider the average days per month staff are absent. This is variable. Staff may work at home even when sick or staff that are sick come to work and don’t report it (but, as a result of both, we still have lower productivity). In such cases, we therefore have an error in sickness reporting. It is important to add error bars, smoothing values and boundaries on graphs to avoid managers reacting wrongly to changes they may see.

Finally, we should consider benchmarking. By this, I mean considering the context of your result. An annual sickness absence per person of 7.5 for staff in a hospital is meaningless unless compared to a similar hospital. Comparison with national statistics or statistics from competitor firms may allow managers to rejoice and move on to something else or to cry with despondency. Benchmarking gives meaning.

After all of these points are considered, you should be clear about what you want to know, how you are characterising the variable(s) and what each depends on. Not until all of this is known should you begin the process of data gathering.

You must gather HR and other personnel-oriented data for a reason. That reason must be steeped in what the firm hopes to achieve – in its strategy – and not in what’s popular. After all, good managers sense their staff. Data gathering and reporting should be done in pursuit of unknowns and deep insight, not what you know already or what you are told in HR ‘best practice’.