What does gender pay gap tell us about society?

What does gender pay gap tell us about society?

Written by Sue Berry on 25th April 2018. Revised 13th January 2021.

10 min read

We know that it’s illegal for firms to pay men and woman differently for the same work. Unless we have a society of law breakers, there’s no pay gap in any firm for the same work done. So, what’s all the noise about. And for all the noise, what does the much-reported-on gender pay gap information really tell us about who we are and how our society works?

About the data gathered

All organisations employing more than 250 people must report their data about gender pay gap. And the Government specifies how the gender pay gap is to be calculated. The current data release is a snapshot of the pay gap situation on 5th April 2017.  The data to be reported only counts those men and women working full time on that day.

The data to be reported only counts those men and women working full time on that day.

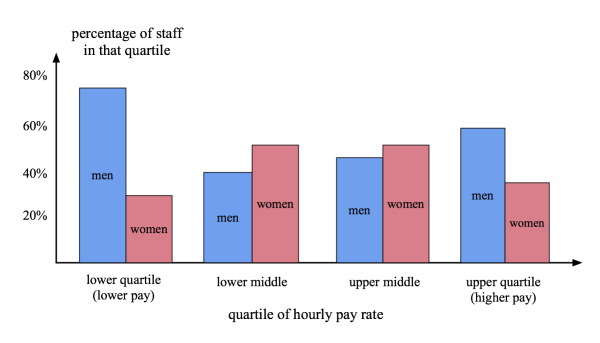

Firstly, the employees in the data set are divided into four equal parts (quartiles). To achieve this, all employees are ranked according to their hourly pay from lowest to highest. An equal number of employees are then allocated to each quartile and the percentage of men and women in each quartile calculated. The results can then be plotted on a chart like the one shown opposite.

This diagram is useful because it tells us the balance between the number of men and women in each of four quartiles across the pay range. For example, when looking (below) at an airline's gender pay gap, we see a larger proportion of men in the (highly paid) upper quartile.

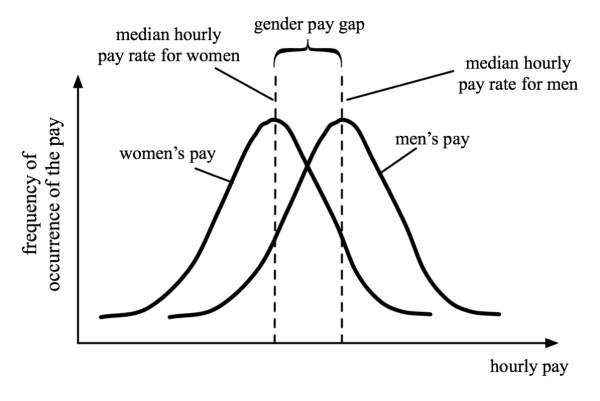

Secondly, further data reports on the mean (or average) difference and the median (middle number) difference in the hourly pay rates for the whole organisation. This calculation shows the gender pay gap for that organisation. Mean and median are used because some organisations will have skewed pay distributions and mean and median together give an idea of this skewedness.

The diagram to the right shows graphically how the gender pay gap will be measured using the difference between the median hourly pay rate for men and for women. The Government stipulates that the gender pay gap should also be calculated using means or averages. In reality of course, in the organisation, the data will be put into MS Excel and formulae will be used to calculate the final values automatically.

Pay quartile data

Let’s take airlines by way of an example.

Let’s take airlines by way of an example.

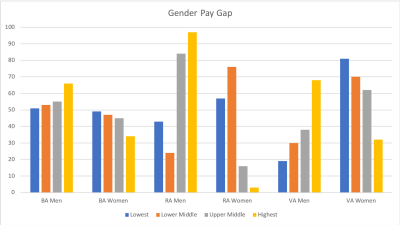

The chart to the left shows the percentage of men and women in each quartile for three well know airlines; British Airways (BA), Ryanair (RA) and Virgin Atlantic/Virgin Holidays (VA).

It is clear in all three airlines that there is a significantly higher percentage of men (than women) earning in the upper quartile – though it is stark in Virgin (VA) and dramatic in Ryanair (RA).

The situation is reversed for the lower middle quartile, with BA having almost the same percentage of men and women in that quartile.

Pay gaps

BA reports a mean gender pay gap of 35% and a median gender pay gap of 10%. Ryanair reports a mean gender pay gap of 67% and a median gender pay gap of 72%. And Virgin reports a mean gender pay gap of 58% and a median gender pay gap of 28%.

A positive pay gap, as illustrated in the data reported above, shows that men are paid more than women in the organisation. And the converse is true. A negative pay gap illustrates that women are paid more than men. There are no negative pay gaps in this data set. And it’s unlikely that there are many negative gender pay gaps across the UK!

So, what does the data tell us?

We know that men and women must be paid equally for jobs of equal value so we can assume that pay discrimination is not the explanation.

But by the measures reported, just about every organisation in the land has a positive gender pay gap – with some very much worse than others. As a society, universally, women are paid less than men. So, what’s going on and why does such a pay gap exist?

Analysing the data

The data shows us that more men are in higher paid jobs in all three airlines. That’s true across the country in most organisations. Stereotypically, more men are appointed as pilots and more women as cabin crew. Pilots are paid more than cabin crew, so we see a gender pay gap. It's clear that over 90% the pilots are male, though lately that ratio is changing as more women see flying as a good career.

Perhaps the gender pay gap data tells us something about an organisation’s hiring activity. For example, a building firm is likely to hire more men as surveyors, project managers and builders simply because men see building as a viable career. The women who do join are likely to be in lower paid support roles, so there’s naturally a big positive gender pay gap.

Likewise, the airline industry recruits more men than women to engineering roles, again simply because more men than women apply. More men than women see aircraft engineering as a viable career. In a meritocracy, you’d expect the pay gap to reflect the ratio of applicants - and it does. This information tells us nothing about the organisation’s pay practices but a lot about who it hires and for what job.

It starts with career choice

Fundamentally, some roles are deemed more valuable than others to organisations. As a result of difference in relative value, doctors get paid more than nurses. Since a high population of women are inclined to join the NHS as nurses this shifts the results to create a positive gender pay gap. So it’s not that men generally get paid more for the same job. The problem is caused by gender bias towards specific careers.

Engineering is another male dominated area. Of the three airlines discussed in this article only Virgin Atlantic report the numbers of male and female engineers in their gender pay report. There are 609 male engineers (90%) and 71 female engineers (10%). And engineering is one of those highly valued, highly paid professions.

Engineering UK in their South East key facts 2017 document shows that 15% of engineering and technology graduates are women. This is generally in line with the proportion of women employed in engineering in Virgin Atlantic. It illustrates the generally lamented issue that engineering, for one reason or another, is a boys domain.

The same is true generally for STEM-related careers (science, technology, engineering and mathematics) across the UK. Both girls and boys have equal interest in those highly paid STEM subjects until around 14 years old. Then girls' interest in STEM subjects wanes. Girls choose subjects that take them into lower paid careers. So, firms looking for employees with high competence in STEM subjects find themselves with more applications from men and therefore more men are recruited. And those organisations will now report a high gender pay gap.

It’s societal. Not organisational.

We’ve highlighted here careers that pay more and where men are more inclined to apply. We've shown that their organisations end up with a gender pay gap. It would seem reasonable that taking the UK as a whole, positive and negative pay gaps would balance out to give a net gender pay gap of zero. In some industries, men would be paid more than women, in others the opposite. But that’s not the case across the whole of the UK. It seems that most organisations have gender pay gaps and the country as a whole has a positive gender pay gap.

Women are generally paid less than men. And there's no point in castigating organisations - they can't fix it. Societal change needs to start in the home and school and in the UK's non-existent careers 'service'. The Government needs policy that fixes the problem at its roots.

Other reasons

Now, we know that our explanation here is not necessarily the whole story. To learn more, the Government must dig deeper. It may well be that in certain industries, women are prevented from progressing within their organization by a male-oriented promotion culture.

It may also be that couples do not share child rearing duties equally - despite the existence now of shared parental leave. If they did, both would take equal time off and both would be be held back equally from progressing in seniority and salary. Instead, it is very likely that the woman always takes time off – simply because culturally that has always been the way. As a result, child-rearing women slip in seniority and hence cause the whole population of women to slip when they eventually return to work.

It is also possible that child-rearing women are discriminated against because they are not able to put in the extra hours that are needed to progress. Women work perhaps their contracted hours but men work 20 or even 30% more and that's highly valued when considering promotion.

In a meritocracy, that slippage is of course acceptable since all appointments and promotions should be made on merit. If a woman is, on return to work, less competent as a result of her not participating in work and development, she should not expect the same pay as a man who stayed in the job and trained.

Of course, the system is a somewhat self-fulfilling prophecy. Because women have lower pay than men, when it comes to a couple deciding who should stay off to rear the child, they quite rationally select the one who causes them least financial damage – the woman.

These other reasons muddy the water. But they don’t disguise the bare facts that there are more men in higher paid jobs and women are disinclined to enter higher paid professions.

And action

Organisations need to ensure that men and women have equal opportunity to apply for roles. But the need for equal opportunity starts much earlier. It’s vital that more young girls are encouraged to keep an interest in STEM subjects through secondary school and beyond.

Many organisations are taking steps to close the gender pay gap by building diverse and inclusive workforces. British Airways, for example, is working to encourage increased numbers of women to take up STEM work-experience placements. And organisations do go into schools to explain to girls how great STEM careers are. But these initiatives will be for nothing if girls are not motivated by their parents and teachers and by society as a whole to consider subjects that in the past have been traditionally seen as ‘boy’ subjects.

Having tackled the low numbers of women applying for high-paid roles, it is then for each organisation to ensure that neither conscous nor unconscious bias impedes a woman’s appointment and progression. The organisational culture must be such that women are not dissuaded from joining in the first place. Once they have joined they must not be penalised when they take a break to have a family.

It will be interesting to see what happens in April 2019 when the next data set is published.

Will we be heading in the right direction, or will the pay gap then suggest that both society and the Government find the problem all just a bit too complicated and long-term?