One of several papers on training and development

Training Effectiveness: ensuring successful skills acquisition

Written by John Berry on 6th May 2017. Revised 16th November 2020.

29 min read

Introduction; what's training to do?

Many staff will be trained at various stages in their professional careers but most will engage in 'sheep dipping' - the idea that someone needs to know how to do something and hence are sent on a course. The hope is that the course does the trick and the person returns to work with the new knowledge, skills and attitudes.

Many staff will be trained at various stages in their professional careers but most will engage in 'sheep dipping' - the idea that someone needs to know how to do something and hence are sent on a course. The hope is that the course does the trick and the person returns to work with the new knowledge, skills and attitudes.

Often though, the sheep dipping fails. The trainee was not motivated to learn, the training activity was poorly targeted, or on return to work the person has changed but the firm is still the same. In these cases all the good work is undone. This paper sets out to describe a better state; a model that a manager can use to design training interventions that will work.

First the paper investigates some of the background to training, the business case for training and why it is that training is the wrong term anyway. It then introduces a model by which a training intervention can be understood. The paper then goes on to describe the three key activities of training and it ends with the conclusion that, despite the difficulties, training of staff is absolutely essential as a method of achieving competitive advantage.

The argument in favour of training staff

Classically firms adopt one of three broad strategic directions - trading on their innovative ideas; driving for high quality in delivered product and service; or seeking to drive down costs so that the firm can trade on price.

Each of these has the people in the business at its heart. Even if the firm is highly automated, it needs people to programme the machines. And firms like hotels and shops critically rely on the human at the point of consumption or transaction - bad service blights the firm. Even in low cost manufacturing and service delivery, people make the difference in cost control. At each stage the competence of staff matters.

So how does training and growth in competence fit with each of the three strategies?

- High competence in an innovation strategy maybe obvious - bring together a highly creative team and you hopefully get product and service innovation. And since markets are fast moving and the environment is changing around the firm and more innovation is needed to keep up to speed, training in the latest knowledge and skills is essential.

- To an extent, having a quality strategy is the same. Unless staff change though, things are maybe a bit more static. A quality strategy involves repeatedly training to the point where delivery teams get it right first time, every time. In such cases the customer buying experience is of the highest value and differentiation is achieved.

- There are several routes to low cost and the following illustrates two. The first is to pay low wages and to drive all costs to minimum with little regard for the people employed. Training most likely doesn't feature. The alternative is to engage with the staff and train to maximise productivity.

In reality, most successful firms will engage in all three of the strategies at various points in time. Product and service development needs innovation for its creation. But then the drive for quality may follow, along with continuous cost reduction. Whether individual or separate strategies, training is a key element in achieving these aims.

The argument against training

Why is it that despite the compelling argument in favour of training, few firms really embrace it as a central part of strategy? There are three possible reasons. Firstly training costs money. It takes time to train on the job, requiring masters to take time out to teach trainees and external courses are costly at an average of about £400 per person per day.

Secondly, once trained, staff will be raring to go with their new skills. If the firm doesn't change in line with this, the trainee will look around for another job in which to use his or her new competence. This leads to a belief amongst managers that there is no point in training staff - they will just leave!

Thirdly, the effects of training are difficult to measure. How does a manager know if the training did indeed result in new behaviour? To do this anything like accurately takes considerable time and skills to the point that few bother trying.

These three reasons lead to a compelling idea that firms should recruit staff with the skills needed and thereafter the firm need make no further investment in its staff. This applies to probably the majority of firms and it is a seriously misplaced idea.

Training to secure competitive advantage

There's a simple phenomenon that we all intuitively know to be correct. It’s that customers buy most from the best firms. That's why they're best after all!! But why would a customer choose one firm over another? The answer's simple - the best firms offer us the goods and services we want at the right price and they offer the best buying experience at the point of sale. These firms have what is termed ‘competitive advantage’.

There's a simple phenomenon that we all intuitively know to be correct. It’s that customers buy most from the best firms. That's why they're best after all!! But why would a customer choose one firm over another? The answer's simple - the best firms offer us the goods and services we want at the right price and they offer the best buying experience at the point of sale. These firms have what is termed ‘competitive advantage’.

We all know competitive advantage when we experience it. But technically it is formed of two parts - the ability of a firm to differentiate its products and services and the ability to control costs so that it has price flexibility. People are a huge influence on product and service differentiation. People are one of the primary mechanisms by which the firm can achieve high productivity and hence minimise costs per unit sold.

If competence exists and people have the necessary skills and knowledge to do a particular job, competitive advantage is achieved. What happens though when competitors improve their products and services? The firm has an existing workforce and needs to have that workforce acquire new competences to stay ahead. If the firm does not act to train its staff, it can only regress to a less competitive position.

You might not yet be convinced - after all a slightly lower position than the competition might be perfectly acceptable. Eventually though, the firm's skills and knowledge will reduce to a point where it can't keep its customers. It moves from profit to loss and the only option is to cut costs through redundancy - the downward spiral has started. Perhaps you'll be convinced then!

Making the business case

The emotive argument is easily made. What of the more objective business case - the return on investment? This is much more difficult because it requires that the manager assesses two cases - the case where investment is made and the case when there is no investment and sales are lost. The manager needs to know how much training investment is needed to stay ahead.

It's a difficult question. It needs the manager to model the various scenarios using the firm's P&L as a simulator.

One possible method is to use the idea of the ‘Delphi oracle’. Get six employees and managers who have a view on the matter (oracles). Set the base case of the P&L for the coming year. Set up a P&L for the two years after that. In parallel set up a model of the market and determine the firm's market share that fuels today's P&L. Then ask the group to discuss and agree the market share if a) competitors stand still, if b) competitors advance through increased competitive advantage and if c) a new, high competence competitor should enter the market. Determine the most likely events and project a P&L for the coming two years. The turnover will logically degrade in line with reduced market share through competitive action by other players. These scenarios are only an example. It's for the group to consider the competitive situation.

Once a benchmark is achieved with the 'do nothing' case, the case where the firm trains its staff can be modelled. The cost of training can be added to the administration costs on the P&L and the viability of improvement through training can be determined. It's seldom the case that training proves non-viable in such analyses!

The key issues

Proving if training is needed and can be justified is straightforward. Determining where training is to be targeted is more difficult. The firm can be thought of as a multi-level system. Senior managers might need training in strategy. Managers may need training in leading teams and in quality systems. And staff may need skills training or training in team-working. Each level affects the others and all training needs to be in pursuit of performance improvement across the firm.

This systems approach to training shows how one can determine what added competence is needed at all levels. When the future involves an improved or new service line, this will affect many people and all will have differing training needs. In a progressive company, training needs must be continually re-assessed.

A high level model for planning training

Models are useful in helping managers understand the various activities that need to be done. Models help managers make sense of what is otherwise a complex and nebulous area - OK, so competence needs to be acquired, but how? What do I do? Simply send people on a course? Or design something in-house?

Models can help managers in determining what needs to be done, the forms of intervention that might be used and how the intervention is evaluated to see what effect it has on the firm's performance. Inevitably therefore, the model also shows the result and hence any additional interventions that are then needed. Setting up training as a series of models has huge benefits, greatest of which is the ability to see progress and hence chart return on training investment.

The model

The model posited here is in three parts and the important thing to grasp from this is that the intervention itself, forming the central element, is not the only important part of training - indeed it could be argued that the activities pre-training and post-training are actually more important. We tend to know what to do in the middle and give little time to the beginning and end.

The first step, pre-training, is important because it affects the motivation of the trainee to learn. Using the 'sheep dip' analogy, if nothing is done before the trainee attends the training activity, they know little of why they are there and what they are to achieve. Potentially they are not well motivated to learn. Personal motivation is fundamental to success during the main training activity.

The second step and main training activity describes the basket of activities that the trainers will run for the trainees. This is described in full later in this paper.

The final step, post-training, is as important as the other two parts. The trainee will come out of the experience with new competencies but unless the trainee's firm plans for their return, there is a serious danger that these competencies will not be usable. The post-training activity also includes evaluation of the intervention. Without evaluation, it's difficult to claim that the intervention has been successful.

Using the model

There are of course many different approaches and single training interventions are linked to others and to the progression of many parallel activities at all levels in the organisation.

The model should be invoked specifically when managers intend buying training from an external training vendor or when intending sending staff on training courses. When used then, it should help managers think about why they are buying training and how they should evaluate the training provider. Managers should note that they are part of the model. One frequent source of training failure is the lack of identification by the trainee's manager of their own role. The manager must be clear of the training objectives, considering the outcomes and behaviours expected after the training. Remember that it is not the training that matters but the outcomes for the trainee. Training is only an input.

Developing training objectives

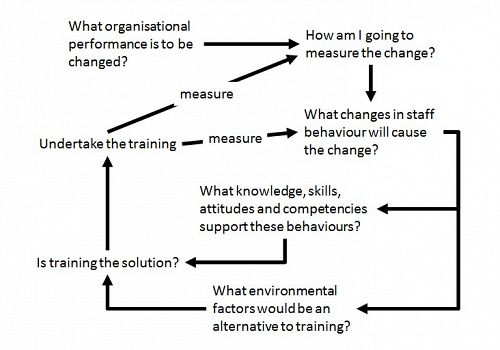

Training aims to change behaviour. The diagram below shows the sort of thought process that a manager might go through when considering a training intervention as solution.

The manager starts at the top and asks what needs to be changed. They then work clockwise to consider if training is the solution and ultimately progress therefore to assess the effect of the training in new behaviours and in change in performance.

Developing desired outcomes

All training investments are made in order to achieve some benefit. Whoever funds the training expects some return on their investment. Training therefore has a desired outcome. It hopes ultimately to effect a change in the trainee's behaviour.

It's important when planning training to be very clear about the new behaviour expected. What is it that is to be done differently and what new standards are to be met? The desired outcomes need to be stated and developed into training objectives so that old behaviour becomes new.

Developing appropriate training objectives

Each training intervention should have one or more training objectives. These training objectives, if met by the training activities, should secure the desired training outcomes. The training intervention itself will be designed to meet these objectives and there will be a mapping between each objective and one or more learning points from the training activities.

When it comes to evaluating training, these training objectives should be used. The evaluation will ask "has each objective been achieved?" This shows how critical it is to develop appropriate training objectives. If these objectives are not correct, the training design will be wrong, the wrong training activities will be delivered, the training will be wrongly evaluated and the desired changes in performance will not be achieved.

Needs assessment

All training should be preceded by a training needs analysis. There is no prescribed way of doing this. In situations where a manager works day-to-day with potential trainees, the manager will take the role of subject matter expert (SME), perceiving gaps in knowledge, skills, attitudes and behaviours in his or her subordinates. These gaps need to be bridged. There are many ways of bridging performance gaps and training may have a role. These gaps can be developed into a statement of training needs.

In situations where workers are remote from managers or where the manager is not a natural SME, other peers and colleagues may take the role in determining what it is the trainees need to aspire to.

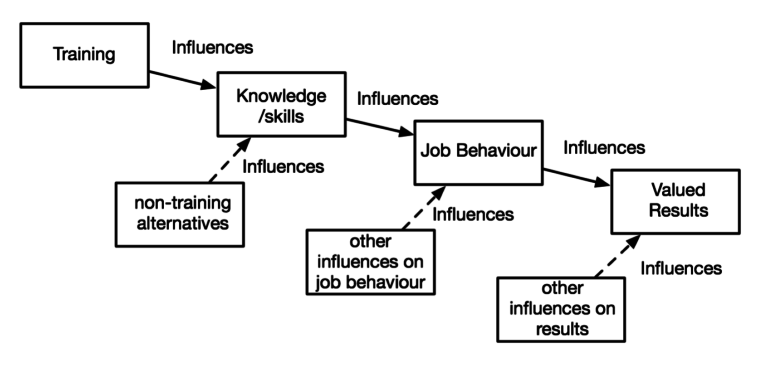

The figure below illustrates a link between the organisationally valued results (the outcomes) and training that might be implemented to achieve these. Working back from right to left, organisationally valued results come from job behaviours. Behaviours are a function of a person's knowledge and skills. If the knowledge and skills are insufficient to cause the necessary behaviours, training may be implemented. The lower boxes show alternatives from the main training-to-values link.

Training needs analysis should be conducted at the individual, team and organisational levels by asking what competencies are needed at each. We give a method of approaching this using a competency framework and details can be found at http://www.timelesstime.co.uk/tools/competency-framework-tool/.

The pre-training activities

As we noted above, training involves three distinct phases or time periods: the period before the trainee attends or experiences the training intervention; the actual intervention; and then the period after. This section centres on the pre-training phase.

Importance of pre-training activities

It's during the pre-training period that the trainee develops their views of the upcoming training intervention. It's in this phase that the motivation to learn is developed and there are specific activities that both trainee and manager can do at this point to optimise the learning outcome.

Good training courses should demand pre-reading. Pre-reading and other pre-course activities that cause trainees to engage with the trainers help to build trust between trainee and trainer, and dispel any myth and concerns that trainees may have. In particular, trainers need to calm fears that trainees may have about their ability to cope with the training. Pre-reading and exercises also give the trainee some idea of how their cognitive abilities and competencies compare with others on the course. From the trainer side, pre-reading sets expectations and allows pre-requites to be learned, thereby avoiding wasted time during the course. An example of this might be in understanding of units of measure in telecommunications. Many trainees arrive with significant weaknesses which waste session time.

Commitment from sponsor

The trainee's sponsor has a significant role. The sponsor is asking the trainee to undertake the learning for a reason and it is critical that this reason is expressed and agreed with the trainee. Reinforcement theory suggests that we all do things to achieve reward from others. Considering this, sponsors need to consider how they will reward the trainee on return to the workplace. Often it is sufficient for the trainee to realise that they have the sponsor's gratitude. In other instances it may be appropriate to link learning and behaviour change to changes in salary. Many firms do this by awarding pay increments for increased competency. The rationale is that the firm makes increased profits by adding to its competency portfolio.

Expectancy theory suggests that the trainee will consider what benefit they are going to accrue from the training. There are two possible sources of benefit: from the firm and from future job prospects outside the firm. The sponsor needs to be sure that there are adequate benefits to be had within the firm otherwise training becomes a means of escape.

Action theory suggests that a goal is achieved through an 'action sequence' of goal setting, mental mapping of the training scenario, monitoring the resultant learning and then receiving feedback on the new competencies and changed behaviour.

The sponsor is instrumental in giving the trainee the mental map of how the training will ensue and how it will develop learning through trainee effort.

Trainee motivation to learn

Trainees have significant capacity for self-direction and self-motivation. People seek the self-satisfaction of achieving valuable goals and conversely they are motivated to do something about sub-standard achievements. The difference between what someone can do today and what they perceive they need to be able to do is a strong motivator to learn. In this pre-training phase managers must help trainees identify these gaps and engender the desire to plug them.

People naturally evaluate their own position using what is known as a negative feedback control model. By evaluating and taking action, people reduce discrepancy between what they can do and what they want to be able to do. If, during this review, the person achieves the desired standard, they do nothing to learn further. This means that one role of the manager is to help the trainee to perceive that there is a gap that needs to be plugged. Generally this is done at appraisal time or during a staff development review. We discuss this in several papers on our web site. This shows that learning requires both discrepancy production (highlighting that there is a gap) and discrepancy reduction (doing something to overcome the lack in competency).

Once the gap is identified and goals set, the trainees’ energies can be mustered to undertake the training and accomplish what they (and hopefully their employer) seek. The setting of goals increases the likelihood that training will be effective.

The training intervention itself

Any training intervention must be designed using activities and methods that are appropriate to achieve the objectives set. No trainee wants to sit through hours of lectures. No trainee wants to practice skills for days on end. No trainee wants to subject themselves to role-play again and again.

Training needs to be fun, interesting and challenging. Trainees do need to work since research shows that without personal effort, the effect of training is reduced. To make training interventions fun, interesting and challenging, a diversity of methods needs to be used which together cover all the necessary learning points.

Trainers need to remember that people learn in different ways. For some it is sufficient to hear an idea and to reflect on it whilst others need to talk about it and to explore the concepts before it makes sense and can be learned. Any intervention into the daily lives the trainees in order to effect learning must consider the ability, personality and motivation of the trainees and in turn how they prefer to learn.

Classroom instruction

Classroom instruction is possibly the most favoured methods of training delivery but it is also possibly the least effective. Here the trainer prepares a lecture using slides to be projected using PowerPoint or other software application via an LCD projector. The trainees listen and, when invited, ask questions to elaborate on any points not understood.

Classroom instruction is possibly the most favoured methods of training delivery but it is also possibly the least effective. Here the trainer prepares a lecture using slides to be projected using PowerPoint or other software application via an LCD projector. The trainees listen and, when invited, ask questions to elaborate on any points not understood.

This method can be effective in achieving the required outcomes but there are several conditions. The first is that the trainer has the capacity to engage with the trainees. Few have that ability and many turn interesting subjects into drudgery with line after line of text projected on a white screen. The second is that the trainees have the cognitive abilities needed to turn what's said into learned skills and knowledge. This form of tuition is inappropriate for many people. One can imagine how someone who prefers learning by doing or learning through discussion with peers would fair. Classroom instruction can be useful but it should always be used with due consideration for the outcomes sought and the trainees concerned.

Classroom instruction should always be mixed with other methods. Typically the trainer should deliver a short session and then task the trainees to undertake some additional activity such as work on an associated case study, a session using a simulator or a group work session where the trainees have a chance to discuss and share experience. The golden rule is 'mix it up'.

Simulations

Simulations are an excellent way of illustrating learning points and allowing trainees to explore sensitivities. A good example is in wireless network design. Here, there is an inverse relationship between the amount of radio spectrum allotted to a network and the number of radio sites needed to serve the geographic area. A simple simulator can be programmed in Excel. Trainees can select an amount of spectrum they want to use and the site count is output by the simulator. Since radio sites represent 60% of the capital cost of the network, the total cost can be determined. Total cost is important in evaluating the business case for new wireless networks – a key learning point in wireless network training.

This example can be made increasingly complex to suit the intended learning points. The area coverage around the wireless network site is a function of the service demanded by subscribers. Typical services include voice, text and data consumed by mobile devices like iPhones and Blackberrys. High bandwidth services like video viewing reduces the coverage and constrains how the spectrum is used. Ultimately in this case, the model becomes very complex with a large number of variables to be considered together. Progressively the simulator can have variables added, starting with a simple device with most variables fixed, growing until it accurately simulates the behaviour of a real network. Trainees can be taken on a journey where complex principles can be simply taught.

Simulators can be designed wherever there is a relationship between variables in physical, social or business phenomena. Further examples include business scenario modelling, perhaps determining market demand for given product pricing mixes and production optimisation for differing materials delivery.

Electronic methods

With the advent of computers and the Internet, training can be delivered in real-time or at a pace set by the trainee.

With the advent of computers and the Internet, training can be delivered in real-time or at a pace set by the trainee.

Real time methods with remote delivery are of particular interest and are used extensively in webinars (seminars using the Internet). Webinars allow many presenters to deliver to many trainees with the trainer and trainee separated geographically by many thousands of kilometres. Here content can be enriched with input from subject matter experts whose attendance in person would not be viable.

Whilst on the face of it this gives great advantage, but there has been little research done to determine webinar effectiveness. With remote trainees listening and watching a delivery on their own, the lead trainer can have little confidence about the effectiveness of delivery. Added steps are essential to determine the learning achieved. Where trainees are grouped together, a local trainer can help assess the success and facilitate with delivery and questions.

Case study: modern wireless networks

This case study is of a course run successfully for several years. It is an off-the-shelf course. In this case the training needs analysis has been completed for a generic trainee and the course is marketed to wireless operators and communications regulators worldwide. This course is interesting because it uses a variety of different training methods and activities.

The course begins with an introductory session which aims to set the scene for the five days ahead. It introduces the lecturers and trainees to one another. The aim of this first session is to settle the trainees and let them understand more of what is ahead. It aims to reinforce what the trainees were told during the pre-training build-up. The rest of the first day comprises lectures and a social event. At the end of the lectures the course case study is introduced on which the trainees will work continually whenever they have spare time.

The second day uses a mix of classroom instruction, group working to reinforce learning points and audio-visual viewing. Where the learning points are complex and potentially difficult for some trainees, simulators are used to allow trainees to explore relationships between variables and to understand concepts in what is otherwise a very difficult subject for many. The second day contains most of the complex technical lectures and it ends with a social function to help trainees relax.

Days three and four use a mix of methods including several hour long group working sessions that seek to exploit the social aspects of learning. During these sessions the trainees work together to plan and evaluate wireless networks. These practical sessions cover aspects which require spatial awareness, something that is difficult to cover adequately in a classroom lecture. Day four ends in a formal dinner.

Day five is shortened to allow travel with most of the morning spent with the trainees presenting case studies. These are simulated pitches to investors to seek support for capital to start various different forms of wireless network. Assessors give comment on how each group performs and on their conclusions, trying to avoid judging content as right or wrong but rather seeking to emphasise, correct and embellish information. Humour is important if this session is to be successful.

The content illustrated above is not important itself. What is important is that a variety of different training methods have been used and the training delivery followed the need to ‘mix things up’. This course consistently gains high scores in evaluations.

On the job

On-the-job training remains one of the most effective methods of training. On-the-job training is a powerful vehicle that allows exemplary behaviour to be observed, mastered and reproduced whilst contributing to the operations of the firm. Many organisations however neither have the skills nor the time to be able to train and coach staff in this way. Most see an external course run by a specialist as an appropriate solution.

A word of warning: on-the-job training does need to be planned just as any other training intervention.

Role play and staged theatre

There are many learning points that are difficult to describe adequately without actually asking the trainees to experience situations. This is particularly relevant when trainees need to understand how other people would react to their actions. Examples here include training in customer relations, giving feedback to others, interpersonal skills and selection interviewing.

There are several tools that can be used here including role-play (using either other trainees or actors) and staged theatre where trainees observe actors and dictate the direction of interpersonal exchanges. These tools allow complex relationships and communications between people to be explored and sensed and feelings to be discussed. Without such methods, trainers would have to rely on the trainees' life experiences to allow them to reflect and learn. For many people this would be difficult.

The post-training activities

There are many alarming statistics quoted about the ineffectiveness of training as measured by the degree to which trainees actually use what they have learned. Where there is poor readiness for the trainee’s return to the workplace, something like only 10% of the learning is transferred to the job. Research suggests that perfect transfer never occurs and figures of around 30 to 40% represent the best one might expect. There is much that can be done and indeed much that must be done to avoid ineffective transfer and to achieve the optimum.

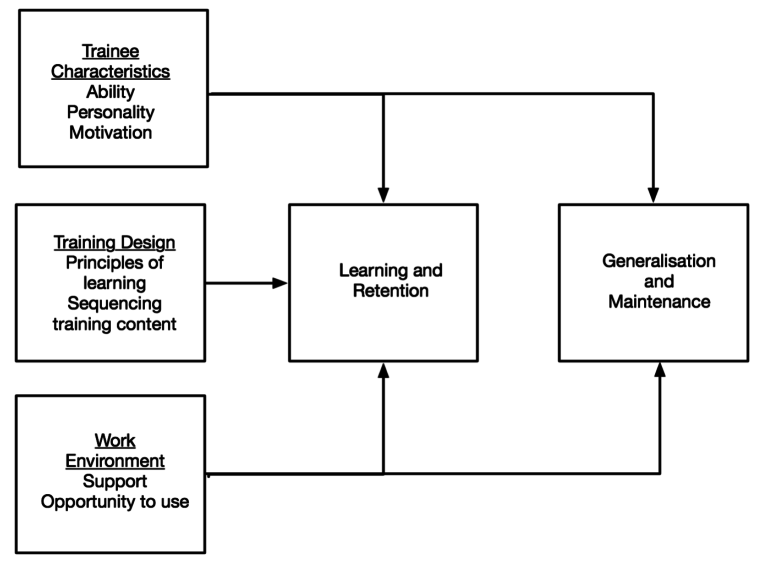

The diagram below illustrates that learning and retention is strongly influenced by the individual's motivation, ability and personality. We discussed the subject of motivation and how this might be improved in the early stages of this paper. There is therefore much that a manager can do to influence the trainees learning and retention.

Preparing for the trainee's return

Transfer of training into the work environment is not likely to be successful unless the supervising manager prepares for the return of the trainee. The trainee will be capable of doing different things and will now think differently. If the manager responds with "I don't care what you were taught on the training, you do things my way", it's unlikely that much will be transferred because the manager is presenting a barrier to new behaviour. If on the other hand the manager encourages the new behaviour and rewards it, then a much more successful state will exist.

The above diagram illustrates the key factors on both learning and retention and on application and maintenance of skills, knowledge, attitudes and behaviours. Both manager and peers must support the new behaviour and the trainee must have adequate opportunity to use their new skills.

Rewards for increased competence

As we noted above, the trainee now has increased competence. He or she needs to be encouraged to use it. He or she must be rewarded for its use. Rewards come in various different forms. Many companies will award a pay rise for increased competence since, in principle, the firm can make more money from that competence. In others this will be inappropriate but reward is nonetheless essential. Reward may mean membership of new groups and networks within the firm or it may simply be in the form of more rewarding work.

Indeed, if a trainee sees no reward for attending the training, the trainee will have little motivation to learn. Reward is an essential part. Expectation of reward must be built in the pre-training phase and the award must be delivered in the post training phase.

Training evaluation

The most common method of evaluating training is to ask the trainee how much they enjoyed the training experience. There is a presumption that if the trainee enjoyed the training, he or she is likely to have learned something. The link between enjoyment and learning is tenuous and uncertain. Just because someone enjoys an experience does not mean that it was meaningful for them. There is argument in training and development research that the trainee is not the best person to judge training effectiveness. Some argue that it should be the trainee’s supervisor or some other objective third party but this has problems too.

Measuring effective learning

All training experiences should be measured for their effectiveness. Few firms do this however. The most likely reason is that it is difficult to do and not an exact science. As a result many consider that it is too expensive and time-consuming. There is no reason to suggest that this should be so. If adequate training objectives are expressed in the pre-training phase, these can in turn be converted into measures.

As an example, if the training objective in a report writing intervention was to be able to structure a report appropriately then evidence can be sought to illustrate that this objective has been achieved. It may be by evaluating future reports structured by the trainee or it may be by setting a test requiring a report to be structured. Either way an assessment can be made.

Taking the training objectives and turning them into measures is a simple and effective way of evaluating the training. It is for the trainer and sponsor then to discuss and determine how this is to be done and what evidence would be acceptable.

Changing the intervention for next time

All training evaluation should contain a part that seeks opportunity for improvement. Any post-training questionnaire should be evaluated and individual parts of the training activities should be scrutinised. Trainers should determine the activities that went well and those that did not. They should determine activities that were successful in achieving objectives and those that were unsuccessful.

There’s a moral obligation on every trainer to try to improve the learning and the intervention should be developed and improved.

Training effectiveness

This paper has addressed the general topic of training. It has suggested that there are three phases in any training activity – pre-training, training and post-training. It is in the pre-training phase that the trainee becomes motivated to learn. It is in the training phase that the trainee has knowledge imparted and learns new skills and adopts new attitudes. And it is in the post-training phase when the trainee brings the new learning to the workplace and applies it to mutual benefit of trainee and employer.

This paper argues that without due attention to and effort in each phase, training will be ineffective.

- Taylor, P., & Driscoll, M. (1998). A new integrated framework for training needs analysis. Human Resource, 8(2), 29-50.

- Clarke, N. (2002). Job / work environment factors influencing training transfer within a human service agency: some indicative support for Baldwin and Ford’s transfer climate construct. International Journal of Training and Development, (1988), 146-162.