Culture Matters: Maximising People Contribution Through Collective Behaviour

Culture Matters: Maximising People Contribution Through Collective Behaviour

Written by John Berry on 5th May 2017. Revised 24th April 2018.

25 min read

Introduction to Culture

What is culture and why does it matter to managers? How is it experienced and how does it influence behaviour? There are simply so many questions making it difficult to know where to start discussing culture. This blog gives helps managers understand and exploit culture, working within existing culture and making change to effect new culture.

What is culture and why does it matter to managers? How is it experienced and how does it influence behaviour? There are simply so many questions making it difficult to know where to start discussing culture. This blog gives helps managers understand and exploit culture, working within existing culture and making change to effect new culture.

Why does culture matter?

Ulsworth and Clegg[1] in a recent paper in the Journal of Occupational and Organisational Psychology discussed why employees take creative or innovative action.

They noted that there were six attributes that, if present, encourage or sponsor employees to act beyond the basic expectation laid out in their job description; six things that would cause the employee to add value to the employer’s business beyond the basics. Each of the six has cultural dimensions: motivation, requirement, cultural support, responsibility, autonomy and time resources. Of course, one of the six, cultural support, centres on culture and describes the climate or environment that needs to be in place for creativity and innovation. If some are missing, and specifically if the culture is wrong, there will be no added value.

This shows culture to be a moderator of other desirable attributes – acting both positively to encourage and negatively to discourage their effect on outcomes. If the right culture exists, those attributes contribute. If the right culture exists, jobs motivate and staff take on more responsibility. If the wrong culture exists, the contribution made is reduced – and in extreme cases, outcomes are prevented. But what is the right or wrong culture?

Defining Culture

Trawling the web yields nine definitions, each useful in setting the scene for further discussion.

- Culture refers to the cumulative deposit of knowledge, experience, beliefs, values, attitudes, meanings, hierarchies, religion, notions of time, roles, spatial relations, concepts of the universe, and material objects and possessions acquired by a group of people in the course of generations through individual and group striving.

- Culture is the systems of knowledge shared by a relatively large group of people.

- Culture is communication, communication is culture.

- Culture in its broadest sense is cultivated behaviour; that is the totality of a person's learned, accumulated experience which is socially transmitted, or more briefly, behaviour through social learning.

- A culture is a way of life of a group of people - the behaviours, beliefs, values, and symbols that they accept, generally without thinking about them, and that are passed along by communication and imitation from one generation to the next.

- Culture is symbolic communication. Some of its symbols include a group's skills, knowledge, attitudes, values, and motives. The meanings of the symbols are learned and deliberately perpetuated in a society through its institutions.

- Culture consists of patterns, explicit and implicit, of and for behaviour acquired and transmitted by symbols, constituting the distinctive achievement of human groups, including their embodiments in artefacts; the essential core of culture consists of traditional ideas and especially their attached values; culture systems may, on the one hand, be considered as products of action, on the other hand, as conditioning influences upon further action.

- Culture is the sum of total of the learned behaviour of a group of people that are generally considered to be the tradition of that people and are transmitted from generation to generation.

- Culture is a collective programming of the mind that distinguishes the members of one group or category of people from another.

Culture exists wherever there is a group of people. Different cultural groups think, feel, and act differently. Each person in the group is able to sense the culture of the moment. Each member of the group affects the group culture and the group culture is changed when any one person leaves the group.

The way we do things around here

Consider the story of the five monkeys. Food is placed high in the monkeys’ cage. Every time they attempt to climb for it they all get sprayed with cold water by the keepers, wherever in cage they are. Eventually they stop trying. Any one monkey who tries is beaten by its fellow monkeys. None of them likes a cold soaking. Then one by one the monkeys are replaced with new monkeys who have not experienced the soaking. Those original monkeys still in the cage prevent the new monkeys from climbing for the food. And even when they have all been replaced, when no original monkeys are in the cage and when none has been soaked, they still prevent one another from climbing. Why? “Because it’s the way we do things round here.”

People function in the same way. So often, employees do things in a particular way because the culture ‘tells them” that’s the way it’s done. And to transgress would be to risk a ‘beating’ even though no-one can quite remember why.

Each individual contributes to group culture. That cultural contribution is developed through personal upbringing, education, community and experience. This means that people in one firm will behave in a unique and common way caused by the unique aggregation of personal contributions. People in the same professions tend to have similar cultural traits brought about through common education. And within firms, one group will behave in a different fashion than others. Cultural behaviour and attitudes come through the door at the start of the working day from such groups as the family and ethnic community current and past. The individual exists in the group culture and contributes to create the group culture.

The individual can assimilate culture, both deliberately and sub-consciously. The Jews from Europe on arrival in the UK in the late part of the nineteenth century onwards did this. They went to Christian schools, quickly became fluent in English and entered ‘normal’ British life[2]. And yet they kept their own ‘Jewishness’ alive and well in the family and continued the traditions of generations at home, living a dual life and a complex culture that adjusted depending on which group they were with. In the same way though, culture can be rejected both deliberately and sub-consciously. Assimilating a firm’s culture is positive. Rejecting a firm’s culture is deeply unhelpful and, as with the Jews, employees can live a dual life apparently assimilating but still rejecting. Culture is truly a complex phenomenon and one that managers need to be sensitive to in order to get the best out of a workforce.

Tacit knowledge of the prevailing culture type helps the individual to cope, adjust and excel in the cultural environment. And it’s the manager’s job to ensure that this happens.

Knowledge of culture and of cultures, combined with awareness and sensing of the cultural environment helps managers get the best out of the people. They can influence the culture to tend to favour particular behaviours that he or she wants in pursuit of corporate goals. Managers must ensure that workplace culture enables desirable attributes like motivation and responsibility.

And finally, in today’s firms, flat structures are popular. Employees are not supervised minute by minute. This simple point about structure suggests that the manager is only one player in constructing the culture. The manager’s leadership approach and day to day management style are contributory to the culture but don’t drive it.

Optimal culture

By now you’ll have the impression that culture is important but perhaps not what it is and how to deal with it as a manager. The rest of this paper discusses firstly how one senses and measures culture. It looks at some of the influences that management has on culture and indeed how wider influences play such as the economy and the pressures of globalised business. The paper then moves on to say what we might want as an optimal culture in the firm and looks at tools that might be used to describe that culture and how it might be achieved. Finally, the paper concludes with an explanation of how managers might effect change in culture by setting culture goals and putting in place a roadmap for change.

The aim of the paper is twofold: to precisely define culture in today’s firm (providing suitable academic rigour and references) and to give managers a working paper to help them understand and effect culture change.

Levels of culture and its management

Culture is like an onion. Consider a nation-state. Peel off a layer or look one level below and one finds several nations, each with a definable culture. In each nation there are many peoples. In each people there are groups and families. At each level the collective groups interact and when they come together they form a culture. As an example, somewhere in the depths of the onion is a collective group of engineers. They belong to several different groups but come together in their profession. Engineers tend to be happy working alone or in groups. They are sensing, thinking people. They are also quite judgemental, keen to reach answers. As a collective group they have similar beliefs, behaviours and traditions that come about through common education and style of work. This culture creates a set of interactions with other groups, conditioned by the engineers’ culture. A firm employing mostly engineers will likely have a culture of sensing, thinking and judging.

Culture is like an onion. Consider a nation-state. Peel off a layer or look one level below and one finds several nations, each with a definable culture. In each nation there are many peoples. In each people there are groups and families. At each level the collective groups interact and when they come together they form a culture. As an example, somewhere in the depths of the onion is a collective group of engineers. They belong to several different groups but come together in their profession. Engineers tend to be happy working alone or in groups. They are sensing, thinking people. They are also quite judgemental, keen to reach answers. As a collective group they have similar beliefs, behaviours and traditions that come about through common education and style of work. This culture creates a set of interactions with other groups, conditioned by the engineers’ culture. A firm employing mostly engineers will likely have a culture of sensing, thinking and judging.

In this example, if a single engineer finds themselves working in a group of accountants, their innate culture will be suppressed or modified. In some way he or she will also affect the innate culture of the accountants to create a distinct culture of this group when it assembles.

Culture can be thought of as existing at:

- The national level: associated with the nation as a whole;

- At the regional level: associated with ethnic, linguistic or religious differences that exist within a nation;

- At the gender level: associated with gender differences (female vs. male);

- At the generation level: associated with the differences between grandparents and parents, parents and children;

- At the social class level: associated with educational opportunities and differences in occupation;

- At the corporate level: associated with the particular culture of an organization and applicable to those who are employed.

Culture is like an onion – or more, it’s a series of intersecting onions, intersecting at every level. The discrete culture at any one point in space (describing the culture in a single firm) is a complex construction of the various contributory cultures. The degree to which any one culture prevails depends on its strength and the receptiveness of those sensing and assimilating it.

The effective culture manager

So far we’ve suggested that culture can be described and later in this paper we see how. We’ve suggested that it can be manipulated within the firm to effect change. So what does a manager need to succeed considering that he manages in a culture and his existence, management action and leadership approach modifies the prevailing culture?

To succeed in managing culture, a manager needs three things.

The first is knowledge of culture, of how it manifests, and the beliefs, behaviours and traditions that can exist. And the manager needs a model for building and expressing their understanding of the culture that prevails presently.

The second essential is a mindfulness of culture and an ability to ‘tune in’ to their surroundings and the firm. This starts with the basic acknowledgement that there is such a thing as culture, that culture in the firm is unique and that it is built from many parts. Sensing can be learned so long as the manager is open to learning.

Finally the manager needs a basket of behaviour or leadership skills and the ability to choose an appropriate behaviour to suit the culture in hand and the culture change desired.

Measuring culture

In the introduction we established that culture affects the way people act. People are driven to act by their motivation. Culture moderates this motivation-behaviour link. Behaviour then, in turn, influences performance on the job. We can say something about the culture by observing a person’s behaviour and assessing their performance output.

We can say something about the prevailing culture by looking at its effects; effectively saying “this culture causes people to...”. Put another way, we can say that people from a given culture typically exhibit a particular behaviour. Again we are describing how the cultural system works by observing its output or the result of its moderating action. We do this using models or ways of looking at complex culture, behaviour and motivation.

The idea of a model

A model is a way of looking at an issue. Models are typically used for describing systems comprising input(s), activity and output(s). Models allow issues to be explored by varying the input or activity and experiencing a change in output. In this case we view the output and speculate about the inputs and activity in order to explore the culture system.

Hofstede's national culture model

The Hofstede model[3] is often used to describe behaviours, beliefs and traditions in nations and peoples. An example is that we might describe Americans as very masculine in that they are very assertive. We likewise might describe Chinese people as not liking to act alone (since they come from a very ‘collective’ culture). The model can be extended to the level of the firm and has some very useful ideas for expressing action in the firm such as decision making.

In the Hofstede model there are six indices: power distance, individualism, masculinity, uncertainty avoidance, orientation and indulgence. These are described below applied to the firm.

Distance Index (PDI) is the extent to which the less powerful members of a firm accept and expect that power is distributed unequally, particularly from senior manager to shop floor worker. This represents inequality, but viewed from below, not from above. It suggests that a firm’s level of inequality is endorsed and legitimised by the employees as much as by the managers. Power distance also shows a shop floor worker the possibility that they could rise to the top. In that sense it is a measure of perceived upward mobility.

Individualism (IDV) has as its opposite, collectivism. Collectivism is the degree to which individuals are integrated into groups. On the individualist side we find firms in which the ties between individuals are loose: everyone is expected to look after him/herself and his/her immediate team. On the collectivist side, we find firms in which people are integrated into strong, cohesive groups, from which they gain protection in exchange for unquestioning loyalty.

Masculinity (MAS) versus its opposite, femininity refers to the degree to which employees exhibit masculine behaviour. Masculine behaviour is often aggressive and assertive whilst feminine behaviour is nurturing. In a masculine environment, problems are solved by argument with some employees exhibiting dominance. Note that a firm with mostly female staff can still be a pretty masculine environment using this definition.

The Uncertainty Avoidance Index (UAI) deals with an employee group’s tolerance for uncertainty and ambiguity; it ultimately refers to man's search for truth. It indicates to what extent a culture programs its members to feel either uncomfortable or comfortable in unstructured situations.

Long-Term Orientation (LTO) versus short-term orientation can be said to deal with virtue regardless of truth. Values associated with Long Term Orientation are thrift and perseverance, perhaps signalling ‘in it for the long haul’. Values associated with Short Term Orientation are respect for tradition, fulfilling social obligations, and protecting one's 'face' perhaps suggesting ‘just get on with it, forget tomorrow’.

Indulgence (IND) versus its opposite, restraint, describes the degree to which the group allows members to enjoy life and have fun as opposed to regulating their behaviour by means of strict social norms within the firm. It’s interesting to also consider this in light of recent research into the work expectations of Generation Y, those born in the 80s and 90s. Generation Y are likely high in indulgence.

The simplest way to apply the Hofstede model is to describe the firm using terms such as ‘tends to’ or ‘tends strongly to’ and to then look at whether this is the culture that management wants or needs for the future of the firm.

Hofstede and others have more recently evolved the national culture model to describe an organisational culture.

Hofstede's organisational culture model

In this organisational culture model there are again six indices.

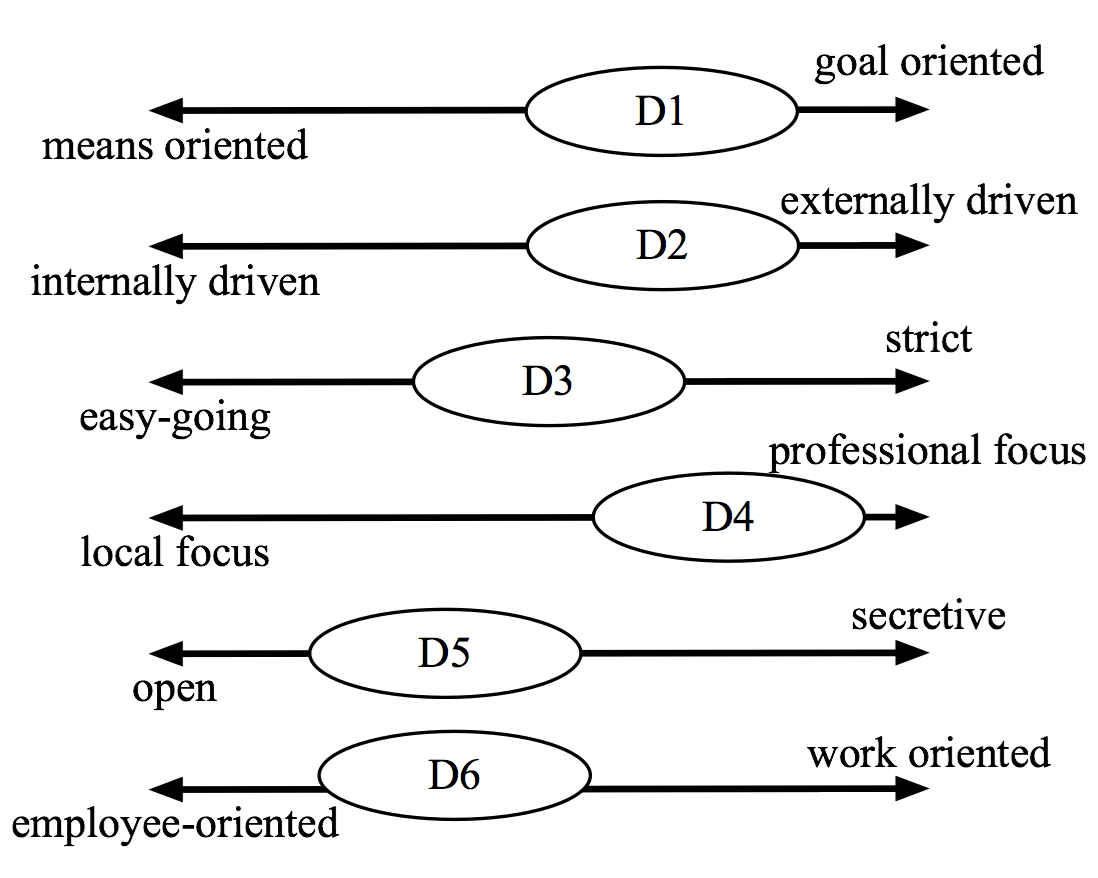

D1 - Means oriented versus goal oriented. Towards a goal-oriented culture, staff are happy to work in the intersts of the organisation rather than their own narrow self-interest. They seek challenging work and wish to be productive. Towards goal orientation is optimal.

D2 - Internally driven versus externally driven. In an externally driven culture staff seek to meet customer demands rather than hiding behind the rules of the organisation. The culture encourages staff to be flexible, acting in the interests of the customer and improvements are always considered possible. Towards internally driven, procedures prevail and the firm considers that it knows what is best for the customer. Clearly one would wish the culture to be towards externally driven.

D3 - Easy going versus strict work discipline. Optimal cultures must have an element of ‘easy going’ in order to provide the right culture to foster innovation. But it can’t be such that the culture extends to be sloppy and wasteful. A mid ground is optimal such that some degree of strictness, cost consciousness and efficiency prevails.

D4 - Local versus professional focus. A professional focus is optimal. Staff need to be encouraged by the culture to think for themselves. They must be critical of themselves and look towards the loing term. The alternative suggests loyalty to the boss and group, focussed on the here and now.

D4 - Local versus professional focus. A professional focus is optimal. Staff need to be encouraged by the culture to think for themselves. They must be critical of themselves and look towards the loing term. The alternative suggests loyalty to the boss and group, focussed on the here and now.

D5 - Open system versus closed system. Closed systems breed secrets. Rumour is the best way to communicate and when the pressure is on and problems occur, they’re hidden. This is clearly not optimal. Staff need to feel that they are welcome whatever tehir contribution. Those who fail are worked with to improve. And feedback to all is the norm.

D6 - Employee oriented versus work oriented. And employee orientation is optimal. This engenders a pleasant work climate with managers taking responsibility for staff welfare. Personal problems are taken into account. Too far towards the alternative – management focus on output at all costs - is narrow minded.

The diagram above shows where, roughly, the organisation’s culture should be (indicated by the ovals positioned between the extremes) for optimal organisational performance.

Some cultural characteristics

It’s worth dwelling at this point to look at some culture traits of one particular national culture that tends to apply across all firms in that country.

- Managers explain tasks clearly, understand employee emotional issues and give support.

- Managers get their hands dirty.

- Loyalty is eroded and employees don't know where their loyalties belong. Weak loyalties are prevailing over older job-for-life norms.

- Time is money. Urgency and deadlines are key. Making work urgent is a deliberate strategy.

- Compensation and benefits are complex with profit related pay and share options.

- Decision making is logical and rational. Facts and evidence important.

- Decent treatment and fairness of employees prevails.

- Empowerment is taking over from hierarchy. Delegation is important. Setting, motivating, and monitoring are used.

- Knowledge-is-power is giving way to a culture where manipulation of information itself is the essence of work.

- Tasks are structuring logically. Behaviour is reserved and indirect approaches favoured. The task becomes the focus.

- Individualism prevails over collectivism. But individuals will cooperate to get the job done.

- Plans are important. Timeliness rules.

- Feedback is provided indirectly and the employee is expected to read between the lines.

- Conflict is distasteful. The prolonged stress and tension of confrontation is dreaded.

- Staff development and succession planning is vogue.

And the country? It’s the United Kingdom. These are cultures or the results of culture that exist in firms in Britain. These are caused by prevailing culture, from the culture norms in the country to the norms in particular work groups. It is for management to determine if these behaviours are desirable or whether a culture change is necessary in order to better meet the firm’s strategy and objectives.

Culture in today's firm

Culture in today’s firm is influenced by a number of things. This section briefly discusses each. The degree to which culture is influenced by these depends on the innate culture in the firm and a great number of external culture factors and personal circumstances.

The pace of business

Time constrains the way decisions are made. It constrains the time available for individual tasks. In turn it is a huge influence upon the culture in the firm. A typical example is that there’s no time now to build friendships whilst at work and hence staff cease to understand one another and cease to rely on one another.

Timeless time

Those working globally and specifically across time zones and across different religious regions will know how the working day extends from when the Japanese start to when the Americans finish – a period of about sixteen hours. And for those dealing with the Arab world, this extends across six of the seven days in every week. Time is timeless. This now presses on the culture in the firm, generating beliefs of unfair treatment and workers are epected to be ‘always on’ duty.

Culture and the economy

In a recession, the culture of a firm will be different from that prevailing in boom times. Culture clash may occur and may be tolerated by employees in a recession when their normal actions are suppressed. Staff are just glad they have a job but they’ll be off to pastures new as soon as things improve. In another sense staff may come to rely on one another more since the prospect of unemployment creates its own bonds and hence behaviours.

Culture in the high skill firm

High skill professionals tend to take many years to be trained. In today’s economy there are skills gaps in many disciplines. This means that management often recognise rare skills and afford this group extra privileges. Whilst the beneficiaries rejoice in their improved state those not so fortunate feel disenfranchised and this reflects overall in the culture with feelings of ‘us and them’. The culture in a non-homogenous and high technology or high skill workforce is particularly complex. A classic example is the culture existing in airlines with pilots and cabin crew forming two distinct cultural groups.

Culture in the service firm

In the service firm, such as perhaps a hotel, the employee pool often comprises low paid, unskilled staff from developing European countries. The obvious result is a unique culture where staff have little loyalty, no expectation of development and perhaps high power-distance. Of course, this must not be allowed to prevail or hotel guests and profits suffer. Ways must be found to enhance staff engagement.

The psychological contract

The psychological contract is the unwritten, implied contract that exists between employee and employer. It is informed by the expectations of both parties. It describes the natural ‘give and take’ of work. Culture is hugely influenced by these unwritten terms defining things like the degree to which the employee will give extra time and the degree to which the employer will allow use of business facilities for family benefit.

The benefits of an optimal culture

This paper has suggested that there is some culture that is optimal for a particular firm. If realised, external culture, employee expectations and firm’s culture are in balance. There is no culture clash and hence all cultural aspects are reinforcing. We’ve suggested here that management can make change to culture in the firm to achieve this balance. This alignment gives tangible benefits and further research into the work of Towers Watson, Denison and IIP will show this quantified. In qualitative terms if the various cultures are aligned and the firm’s strategy is in concert with the culture, employees will be optimally motivated to contribute to the firm’s strategy.

A roadmap for change

So how does management effect culture change? Culture does not change overnight. Culture does not change with one single action. As a complex set of beliefs, behaviours and traditions it must be engineered to change through a long term and decisive culture change project. This project must contain the following elements.

Initial data gathering

The start point is the culture audit. Denison offers this and the other models cited above can also be used to assess where the firm is now.

Where are we now?

There’s a presumption that management have a problem. Something is not right in order to have management feel it needs to initiate the culture assessment and the culture change project. It could be a feeling that staff are not behaving correctly and sales are being lost as a result. It could be that staff are leaving and the firm has a problem recruiting to replace. Whatever the issue is, the classic consulting lifecycle can be used.

This begins with the development of a hypothesis (or speculation about the cause). From this, management can develop further sub-hypotheses. The audit or survey is then used to gather evidence in support of the hypothesis. If ultimately the hypothesis is disproved by the evidence then speculation needs to begin again. This ‘where are we now’ stage ends once the hypothesis is proven and the root cause(s) are established.

Where do we want to be and why?

The next stage is to vocalise where the firm wants to be as regards culture. This can best be done by telling a story: “we believe we want to achieve a state where employees and managers...”. This statement should go on to describe the behaviours, beliefs and traditions that management believe are right to support the firm’s strategic goals.

Ideally this vision statement for culture should be described in the same terms used to evaluate the current culture effectively creating a common currency for the project.

Main data gathering

Nothing can happen until data has been gathered to model the culture currently in place and to determine the changes to each of the culture attributes. Refer back to the various models for ways of expressing the current culture and the desired future culture. At the end of this stage management should have an accurate model of the state before and after change actions.

How do we get there?

It is then a question of proposing change activity and evaluating the activity to confirm that it would likely have the desired effect in moving the firm towards its just culture.

This then becomes the culture change plan.

What steps are there along the way?

As with any plan, the resulting action and outcomes need to be evaluated along the way to repeatedly ask “are we getting there” and “did that last action have the desired effect”. Simply there needs to be continuous progress assessment.

Some tenets

There are three core tenets or truisms - three things that have to be in place. If they are missing or not acknowledged and accepted in the culture change project, the project will fail.

- Change comes from the top

If the boss does not believe in the need for change and potentially the need for change in his or her approach and day to day management styles, the project is doomed.

2. Change takes time

No one action taken on its own to change culture will be the panacea. The project will likely contain tens of individual changes over a period of time. One year is typical in order to see tangible outcome and perhaps two to three years to see a lasting change.

3. Example leads change

Change comes easy if the key players lead by example. Unlike the situation where the monkeys accepted the culture, if a manager explains why the change is necessary and leads by example, a positive outcome is more likely.

Conclusions

This paper has addressed culture; what it is, how an employee senses culture and the traits needed in managers to sense and work with culture to optimise the business result given a prevailing culture. It has discussed some typical cultures in today’s firms and the pressures on the firm that ‘make’ culture in the modern globalised business environment. It has expressed the concept of an optimal culture and suggested how management goes about quantifying this and setting plans to achieve it. Finally, it described how to set about creating a culture change project in order to move from where the firm is today to some other culture tomorrow.

Culture is a complex thing. It has many facets. There is however a huge body of knowledge existing that aids culture practitioners in making culture change to the benefit of the firm.

TimelesTime is expert in culture change. Its consultants have effected change is many organisations and can manage change for any form and size of firm. In sensing and dealing with a firm’s culture, it is difficult for management to take and objective view. People consultants have a clear role to play.

- Ulsworth KL & Clegg CJ (2010), Why employees undertake creative action?, Journal of Occupational and Organizational Psychology, pp77-99, Volume 83, Part 1, March 2010, The British Psychological Society.

- Sacks, J (2007), The Home We build Together, pp27-30, Continuum, London.

- For further information see http://www.geert-hofstede.com/ accessed on 24th April 2018.