One of several papers on operations

Business Continuity: keeping organisations working come what may

Written by Sue Berry on 1st May 2017. Revised 27th October 2020.

11 min read

Introduction

In this age of computerisation of nearly every function we do, organisations are more vulnerable than ever to disruption of normal business. There is unfortunately much myth and misunderstanding centring on the belief that if the computer system is protected, backed up and duplicated, all will be well.

Actually it is people that are key to every business. This means people are the most likely cause of disruption and in risk terms, afford the greatest risk to the organisation's business continuity. One has to put this in context or we may be at risk of never employing anyone. Take a couple of the recent problems: striking public transport workers and swine flu. In the former case, the disruption is caused by the workforce not being able to get to the business without significant personal effort. In the latter, the workforce is struck down with flu and there’s nothing anyone can do. Or is there?

People are the main risk to a business – and yet they also offer many solutions to business continuity. This paper addresses how one goes about building a Business Continuity Management Plan and how one subsequently manages that plan to assure minimal down time. It uses some of the established best practice and provides references for further reading.

Business Continuity Planning

This method of developing a plan follows the BSI Guidelines[1] and the BS25999[2] nomenclature (see now ISO22301). It gives a step-by-step guide to the whole process of developing your BCP. Whilst its primary interest is the people aspects of business, it is valid for all aspects.

The paper will use a holistic process to identify potential impacts that threaten an organisation. It provides a framework for building resilience and developing a capability for an effective response that safeguards key stakeholders, reputation, brand and value-creating activities. The resulting document forms the HR Business Continuity Management (BCM) plan.

As well as developing organisation-resilience to survive loss of some, or all of operational capability and equipment, there is a requirement to consider surviving significant loss of people resources and loss of reputation. In addition to the two latter categories, people also have a major effect on the operational capability through inefficiency, negligence or malicious act. All of these consequences are quantifiable in financial terms.

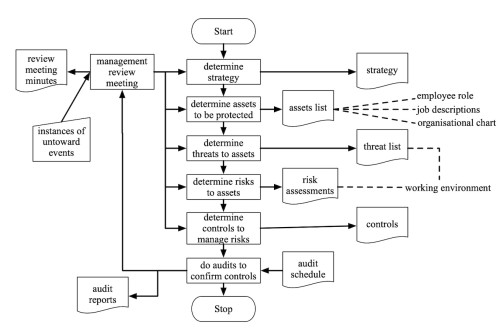

The following diagram shows the overall process for developing a plan. Each element will now be considered in turn.

The process starts with identification of business need for continuity. It’s easy to be carried away with BCP but everything spent should be targeted towards controlling some risk or other that is considered important to the business stakeholders. The process ends with completion of audits to make sure the whole process will work if called on.

Activities are shown as rectangles and documents and data repositories are shown as rectangles with a wavy base. The process flows from top to bottom.

Process for developing an HR-Oriented BCM Plan

The following is a step by step process. Follow it faithfully and you will end with a BCP. Do however be careful to start at the beginning or you will fall into the trap of presuming the initial requirements and reason for the BCP in the first place.

Identifying Business Need

This can be captured in a succinct statement. State the processes that are critical to maintain. There is no focus at this point, simply establish what is important to the business. You'll see that the business strategy links in to this because there is no point in guarding something that is not part of your strategy.

In a charity that re-homes stray and abandoned dogs, there are two activities that are critical to the business – raising money and re-homing dogs. Other activities might aid these two but really, they are the only things that matter to the charity.

Defining Business Assets

From the processes that are critical to maintain and protect, identify the assets which are part of these processes. These must be protected from destruction or corruption and the whole process must be protected against interruption.

The business assets are much wider than software, hardware and data systems infrastructure. These aspects make up the IT element of the asset register, but the asset list is much larger for most firms.

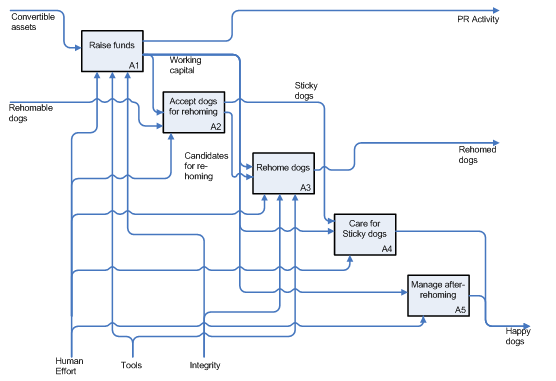

A good tool in analysing businesses is the business process analysis. The example below uses the IDEF0[3] method.

In this diagram, processes are rectangles, inputs (entities or assets) enter from the left and outputs (entities or assets) exit to the right. Enablers (entities or assets) enter from the bottom. It shows that the business begins with convertible assets which enter the system in A1, the end process is happy dogs as an output after re-homing at A5. It is clear to see that without funding the organisation will not function. The enablers to the system are human effort, tools and integrity – each have an effect on the system as described below:

- Human effort impacts the raising of funds (A1) since without the fundraisers the organisation will have no income. They also impact the care of dogs (A4) and the post re-homing process (A5).

- Tools are needed to manage the fundraising (A1) and to manage the re-homing process (A3). The donor database is fundamental to the administration of both activities; it is a key asset to be protected.

- Integrity impacts on A1 and A3. Loss of reputation will result in loss of income and less clients to take dogs.

By identifying all key assets and functions first, the assets to be protected become clear.

Determining the Risks

The next step is to identify the risks to the assets and processes. By far the biggest risk is always associated with people. Humans produce and control many assets and these are generally the most vulnerable.

In order to understand the implications of the risks, they need to be scored in some quantitative way. The normal method is to multiply the chance that they will occur by the severity of effect on the business if they do occur. Chance is a factor between 0 and 1 with 1 representing certainty and a low number representing a very low probability. It is chance that a specified untoward event (that causes loss or degradation of asset) occurs. The severity is normally measured in money terms and is the cost to you of losing the asset.

Once multiplied, select a threshold above which you will expect the BCP to control the loss. Then make a plan to cover the risks. Below the threshold accept the risk. You have to score on a single uniform metric for all assets. One way of looking at the loss is loss of future earnings to the business. For example, anything at or above £25k (when multiplied) requires control.

Risk Register

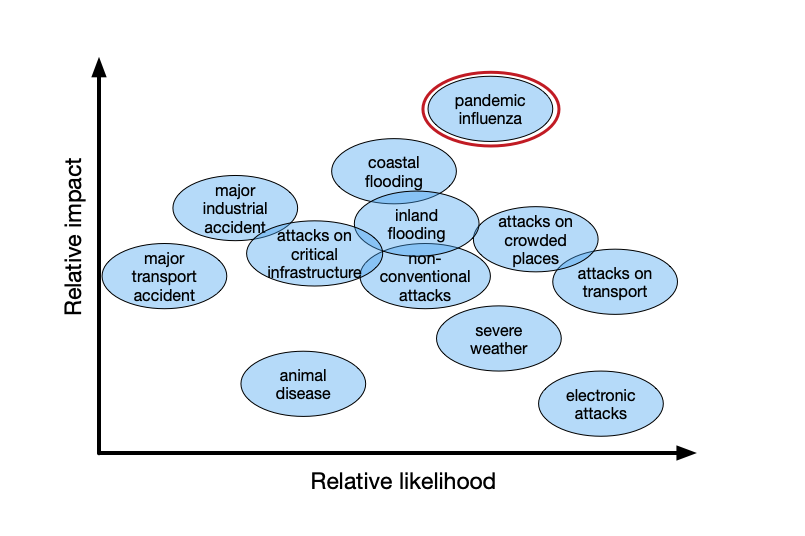

The Government discusses risk and severity of effect in its National Risk Register document[4]. The summary diagram is shown adjacent. In addition, your organisation will have further risks unique to its operation which need to be captured. Don’t forget that the most likely events are things like loss of telephones or strikes causing problems for staff attendance. A small, local event can cause more loss than a very unlikely national event.

Using government data and your own specific risks a risk register can be developed. An example is shown below.

| Event | Probability of occurrance | Severity of occurrence (£) | Composit Score (PxS) | Mitigation, control or plan |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Denied staff effort through loss of public transport | 30% | 1 day £x | £y | action to be taken |

| Loss of reputation caused by bad publicity about dog treatment | 0.1% | £500k | £500 | Accept |

| Disgruntled employee spreads bad press about the organisation | 1% | £ | £ | Accept or action to take |

Developing Controls

Having determined the risks, controls must be developed to manage them. There will be many risks which are acceptable. Others must be controlled such that the loss moves below the threshold.

There are several people oriented controls. The most obvious is the employment contract. This has many expressed and implied controls including the obligation of confidentiality about the employer’s business. It also should prevent involvement with competitors and other conflicts of interests. Less obvious are the policies, procedures and guidelines that form the basis of HR management. An example is the Disciplinary Procedure that sets out the employer’s right to dismiss employees for gross misconduct. These signal to the employee that certain behaviour is not acceptable and act as both deterrent and control.

There are of course more effective controls such as the benefits and remuneration system and with it the system of communications within the organisation. Someone who feels committed to a good employer is more likely to accept a requirement to struggle in to work during heavy snow than someone who is treated poorly.

For staff that need not always be in the workplace, permitting periodic working from home is a form of control. Every day an employee uses their laptop at home, logging on over their home broadband they are testing their ability to continue working when disruption strikes. Trust given to these employees will be re-paid many times provided that it is given in the right way.

Conducting Audits

There are two aspects to audit. The first is the initial evaluation to determine that the controls will take the effect planned. Secondly, once developed the system should be audited on a regular basis in order to ensure it is fit for purpose. The BCP must be a living document that is frequently reviewed and tested.

When Government Takes Control

The Coronavirus pandemic illustrated just how unprepared businesses were. The following gives a brief commentary and explanation of what happened in spring and summer 2020 and how this integrates with the above guidance.

Firstly, the obvious. Firms had very little resilience.

At one end of the resilience scale were firms that had no reserves and existed from day to day – the so-called zombie companies. They are exemplified by the big rise in insolvencies in March as the Coronavirus hit.

In the middle of the resilience scale are firms that had a few months' cover for costs and who would have gone bust without the Government’s Coronavirus Job Retention Scheme and other support.

And finally, at the robust end of the resilience scale there are those firms that had enough to carry on. Resilience for firms starts with having financial reserves that give them manoeuvring room when catastrophe strikes.

Secondly, every organisation, large and small, departed from the process outlined in the first part of this blog.

We discussed above that firms must analyse their business to find threats and then look at risks. In the Coronavirus pandemic, the hazard was obvious – SARS-CoV-2. The risk was the chance of infection with COVID-19. The severity of outcome was such that the Government took over the early part of the BCP process.

Government scientists determined the risk, and set out the controls necessary.

At that point confusion reigned, since the traditional risk assessment and control sequence went out the window. It was replaced by guidelines: isolate if you feel unwell, work from home if possible, keep two metres apart, wash your hands and don’t touch your face.

As the number of deaths reduced, so the advice relaxed: meet only in small groups, go to work but don’t face co-workers and wear a mask on public transport.

Effectively, managers’ responsibility for health and safety was usurped by the Government. The Government told firms what to do – even to the point of telling them when they must close, and when they could open.

The situation was unusual. In this case, managers’ responsibility became compliance with Government guidelines. And audits were done against those guidelines and not against firm’s own thought-through controls.

Exceptional times!

Meanwhile all the other risks remained and the above process still applied. Firms were effectively running a two-tier risk management process – one under their control, and the other where they did what they were told.

Conclusion

Business continuity plans should be developed for all organisations. They are relatively simple to develop and almost always involve risk control that centres around people.

There is much myth and those from the ICT world will tell you that BCP works only in the ICT domain. That’s too black and white. BCP is also a people thing with people risks and people controls. The Coronavirus pandemic exemplified that.

People can do huge damage to an organisation, both from within as employees and from outside as customers and stakeholders. And yet people within an organisation can protect that organisation when disaster strikes. What is needed is a work programme such as that given in Figure 1 of this white paper.

Working diligently to this framework will give an organisation the protection it needs.

And now?

TimelessTime has many years of experience putting the HR elements of Business Continuity in place and ensuring they are effective. Contact us today.

- Good Practice Guidelines 2008: A Management Guide to Implementing Good Practice in Business Continuity Management, Version 2008.1, The Business Continuity Institute

- BS25999 Business Continuity /Management-systems/Standards-and-Schemes/BS-25999/ (Accessed 24 October 2009)

- IDEF – Integrated Definition Methods (www.idef.com Accessed 24 October 2009)

- National Risk Register, Cabinet Office, 2008 (Accessed 8th October 2009) This is now a broken link - checked 04.04.11